I was seven before I knew that the proper way to sweep a chimney was not with a burning holly bush tied to the end of a bean stick. On the edge of the New Forest, my grandparents’ cottage was number six in a terrace of eight and it is a wonder that the whole terrace didn’t catch fire regularly. Although my grandmother, whose word was law, would undoubtedly have refused it permission to do so!

I was seven before I knew that the proper way to sweep a chimney was not with a burning holly bush tied to the end of a bean stick. On the edge of the New Forest, my grandparents’ cottage was number six in a terrace of eight and it is a wonder that the whole terrace didn’t catch fire regularly. Although my grandmother, whose word was law, would undoubtedly have refused it permission to do so!

In spite of this seeming disregard for fire safety, she refused to have a gas stove in the house for fear of explosion. Instead, she persuaded my grandfather (and the landlord) that a corrugated iron porch should be built onto the backdoor and the stove housed in it.

The arrival of the gas stove, together with the already installed central light bulb in each of the two up, two down rooms, provided the only mod cons in the cottage until the mid 1950s. There were two taps between the eight houses, one at each end of the block, but no mains drainage. Waste water was either thrown on the garden, or poured into one of two soakaways, one of which my grandparents had the doubtful privilege of having in their garden.

At least each cottage did have its own bucket lavatory, in the woodshed cum coalhouse at the far end of the long back garden, and the collection cart came round about four in the morning to empty the buckets put out the previous night. One morning, after celebrating late into the night – what, we never heard – one of the night soil collectors forgot to let go of the bucket as he threw the contents into the cart and…

By 1943, the cottage – which by then should have housed only my grandparents -had filled up with their children and families escaping from the blitz in Southampton and London. The regular quota of occupants was four adults, me and a baby cousin. With husbands returning from Air Force and police leave, this often increased to nine or even ten. Space in the small back room was very limited, the front room, of course, only being used by the family on Sundays, although it was occasionally utilised as an extra bedroom.

So with this shortage of space, my grandmother, nothing daunted, took to doing the whole family’s washing every Monday in the garden shed, carrying cold water from four houses away to be heated on the stove and then taken to the tin bath in the shed.

My grandfather, in his early sixties, was quite happy to leave all the domestic arrangements to her. He was the town postman and every weekday got up at 4am so he could be ready to receive the post from Salisbury and have it sorted ready for the morning deliveries. Gran got up with him and used the time until the rest of the family surfaced to clean the cottage. On more than one occasion we found she had given the entire back room a new coat of paint before we were up at seven o’clock.

Granddad would come home for a cup of tea at about ten o’clock, together with any other postmen who happened to be in the area. He would then set out on his delivery riding his regulation red bicycle. Until I started school he frequently slung his bag on his back and took me with him, sitting on the flat platform in front of the handlebars, and hanging on for dear life. I only fell off once. After that they decided that perhaps it would be safer if I was strapped on! When he had finished the round we’d go back to the Post Office and I’d happily draw, sitting on the swinging seats used by the sorters.

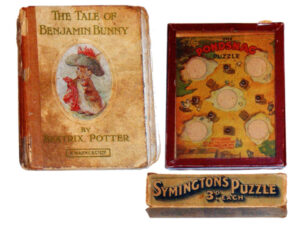

As a young child ‘war time’ was normal. Anything that occurred before had happened in the olden days! Lack of new toys, second-hand books, which came via the Red Cross, or a fourth birthday cake consisting of a current bun with four candles on it, didn’t seem out of place at all.

Although my mother must have felt awful when my comment on the latter was, “That’s a funny birthday cake.”

I did, however, have a delightful birthday present, a second-hand tricycle, on which I spent many hours cycling round the block dressed in what had become known, courtesy of Winston Churchill, as a siren suit.

We weren’t totally isolated from the war. Every Tuesday my mother went to Southampton, even at the height of the blitz, to see my father, a DS in the police. On several occasions when she took me with her we ended the day by spending time in an air raid shelter. Evidently on one of these visits, at the age of two, I reduced an aunt to tears when on hearing the siren I clamped my hands on my head and bolted down the garden shouting, “Quick, bombs, shelter!”

Possibly the greatest impact that the war made on the townsfolk was the arrival of the Americans. They were housed in the church hall, which was opposite the front of the terrace. Gran, who had been the cleaner and caretaker of the hall for many years, was somewhat affronted by this takeover but soon took one young soldier under her wing. He would come in for meals, or just to sit in front of the fire and chat. But above all, as far as I was concerned, Uncle Bob was a great favourite as he brought sweets and also chewing gum – much despised by the adults!

After the war, Bob’s mother wrote to my grandmother thanking her for her kindness while her son was so far from home and the two became lifelong pen friends. On Christmas Day in 1945, food parcels arrived from the USA containing not only sweets, but also tins – several of which had the emotive label ‘Boiled Dinner’!

When D-Day arrived everyone in the terrace was euphoric and all the younger members paraded up and down the back gardens singing Roll out the Barrel playing anything that would serve as a makeshift instrument. I had a comb and paper!

By the spring of 1945, when it became obvious that the war was drawing to a close and life in the towns was safer, the extended family left the peace of the New Forest, leaving my grandparents to a well-earned retirement,

Valerie Phipps, Barnstaple, Devon