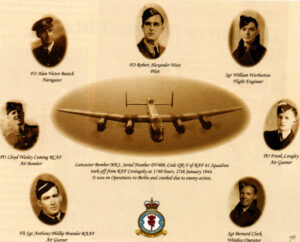

On December 16th, 1943, nearly 500 heavy bombers left eastern England on a mission to bomb Berlin. More than 300 men lost their lives, many because of the dreadful weather back in England. My uncle, Bill Warburton, was Flight Engineer on one of the surviving planes. His young crew knew only too well that they would be lucky to survive nine missions – and on January 27th, 1944, they lost their lives on another raid to Berlin.

Some 60 years on, I spent a year tracing the relatives of every crew member and eventually I succeeded.

I brought the families together to share and exchange information.

The diary kept by Wireless Operator Sgt Bernard Clark has survived and takes the reader graphically back.

‘…Better morning as regards weather. Good news, ops on. Berlin for our first op. Ops breakfast of egg and bacon, bread and butter and coffee.

‘Dashed off to change into long underwear. Phil collected coffee and orange, back to the crew room and final briefing, then out to the aircraft with half an hour to go to zero.

‘All excited, engines revved up and down the taxi path with a full load of bombs. Quite a crowd to cheer us off at 6.40pm, climbing up – and up – and then the first snag. Monica (device for locating enemy aircraft) packs in on one side. I go back to check and find the fuselage door open. The wind pressure was terrific; I can only just close the door but cannot fasten it, so back comes Bill with a rope and ties up the door.

‘I manage to get Monica working and everything seems grand with first contact with base. Next thing we are over the coast near Amsterdam, tons of cloud and some flak bursting: on to Berlin at about 21,000ft.

‘Not very cold: We appear to be well on time and in the stream OK, in between Bremen and Hanover right on the markers and bang on track. Lots of flares but cloud too thick for searchlights, up comes the target right on time.

‘Rear gunner Frank on the intercom says he has trouble with the oxygen and is feeling awful. Bob (Pilot) asks him to hang on till off the target if possible and on we go. Lloyd spies the target markers and we fly level on to them and zump! Bombs gone.

‘There was a faint call for help from Frank – lots of gurgles over the intercom. Armed with a portable bottle (oxygen) I went to the back of aircraft with a torch. The back door was still open about two inches and the wind came through like a knife.

‘I managed to open Frank’s doors in his turret. I stretched up and tried to break ice from his oxygen mask. I could see flares and lights outside like November 5th.

‘Frank, although almost out, turned his turret in the direction of the tracer on the port beam, and I was trapped by my arm in between the turret and the rear of the fuselage. I felt scared because I only had two minutes left in my oxygen bottle.

‘I struggled out but dropped my torch and lost it. After what seemed an age I plugged my oxygen tube into the Elsan spare and recovered my breath a bit. It was hellish cold although it was only 25 degrees below on the gauge.

‘I struggled back to my place and told Bob how hopeless things were with Frank. (We were still in the flack and flares area, one whizzing by our tail).

‘Bob gave me a long oxygen tube and taking two or three portable bottles and another torch. I went back to see Frank. He was just about all out. I got his doors open again and pulled him flat on his back on the wooden plank (from his turret to the tail cross-member) then pulled his oxygen mask off and plugged the spare one on to the Elsan oxygen point and popped the new mask on his face. After about five minutes he began to flicker his eyes about and try to sit up, but I made him lay still. I told him to take his time then get back into his turret leaving the door open, still using the spare mask.

‘I then went up to the front and started to work again. We just missed Rostock – on to Denmark and out over the North Sea with lots of flack on the Danish coast. Bob had come down several thousand feet to help Frank, but we dived through the barrage.

‘Frank gradually got back to normal, except his electrical suit did not work and he was very cold; we carried on until we got just off the coast near Cromer. The cloud was only 700 ft high so we kept on until we got back to base.

‘Base gave us no.7 position and in we came to make a wizard landing about 12.39 midnight. The ground crew cheered us in and we soon got down to breakfast after interrogation. We eventually got into bed at 2.45am.

‘So ended our first operational trip, though Bob had already had his baptism of fire at Leipzig. Frank soon felt better.’

The crew went on leave for Christmas. After leave, they completed just seven more operations.