Most of us know about fear. In my lifetime I’ve often been frightened, and few people can have managed to avoid being afraid altogether. Undoubtedly fear has many guises. Some people hate spiders; a well-known war hero apparently confessed to being dreadfully afraid of being alone in the dark; and how many normal people would ever happily climb a factory chimney without being afraid? I wouldn’t do it for a start.

In my case, almost without thinking, I came face to face with a particular fear and, although I got over it slowly in my own way, the memory stayed with me for many years. Even now, although it happened perhaps 50 years ago, the thought occasionally still surfaces.

The year was 1950, and I was working as a very young merchant seaman on a cargo ship en route to the West African coast. It was my watch on deck, at about 04.15, and my look-out station was right in the ‘eyes’ of the foc’sle head. The night was like velvet, warm and totally soft. Up in the bows one couldn’t even hear the metronomic ‘thud’ of the main engine which permeated aft.

Having just been promoted to watch duties after seven months as a deck boy, I was very keen. As most old hands will tell you, if you want the straightest bow-wave forget the quartermaster: give the job to the first tripper while boredom has yet to take over his mind…

On British ships at that time the look-out watched for lights, any small or large craft in view, or any unusual happenings or events. Generally it wasn’t madly exciting, but a good look-out was essential. Ask the old salts who sailed through ‘U-boat Alley’ just a few hours before in those days! A good look-around fully from left to right and back was normal then, and we still kept that type of watch.

However, on the early morning in question I heard loud splashes deep at the bow-wave, and looking right down at the water line, perhaps 15ft. below me, I saw a large group of porpoises playing. They looked magnificent, perhaps a dozen of them, weaving and swerving in unison.

Even as I looked, the bow began glowing with phosphorus as the marine mammals zoomed below me. My view was marvellous of course, but being alone with no-one closer to me than 200ft. or so from the distant bridge, I couldn’t share a moment of it with anyone.

I suppose I’d been watching them for a good five minutes when I thought about my watch duties. Amazingly, it was only then that I looked around again and realised just how careless I had become. So engrossed had I been that I’d swung my legs fully to one side and, without thinking.was now balancing on the broad sloping part of the bow itself, sitting ‘no hands’ and simply moving with the roll of the vessel carrying my weight, but gaining no means of a safe return to an upright position. One slip and I would have been off….

My blood ran cold. It seemed an age before the ship rolled slowly and back far enough for me to lean gingerly inboard and get some purchase with my fingertips. All this happened in a matter of seconds, but it seemed an age to me. All I could think about was the fact that no-one would ever know why I had apparently jumped. Who else could know what had been in my mind?

Hardly daring to breathe, I inched my weight back a little at a time, praying that I wouldn’t slip on the salty metal each time I moved. Eventually I could carefully touch a slender wire by the jack-staff. At that point I could hold on and swing my legs inboard again. After that, my return to the deck was quite easily managed, but the fear stayed with me for a long time.

Although I made several trips to sea after that, never again did I put myself on that slippery slope, and strangely, nor did I ever tell any of my shipmates about my close escape. It was something I kept to myself for one reason alone. I couldn’t believe how stupid I’d been to sit there!

had I carelessly fallen or slipped overboard at that point on that early morning, my chances of rescue would have been extremely small. There were only two other sailors awake on deck at that time. One on the wheel, who would not have been able to see me from the vantage point, and one on ‘stand-by’ in the crew messroom. The officer of the watch would almost certainly have been in the chartroom.

As I’ve often said to myself since, it was such a lovely night, but it could so easily have been my last.

I still feel the sweat on my palms when I think of it, even now, after almost 50 years.

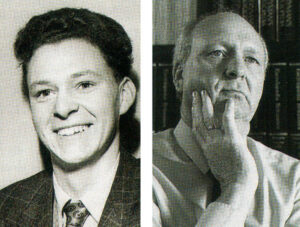

Stan Nelson