No-one knew why my father, who was born in 1880, was christened Orloff. Possibly his mother, who had at least 14 children, ran out of names or maybe at the time of his birth she was reading a novel about a Russian family, but we all got used to hearing him called by that name.

However, he was an extremely hard-work-ing person who took little rest from his labours. As well as his job as a solicitor’s clerk for 50 years, he taught shorthand at the local technical college on several evenings a week and acted as secretary to the local branch of the Foresters as well as being voluntary secretary of the Yeovil Fire Brigade.

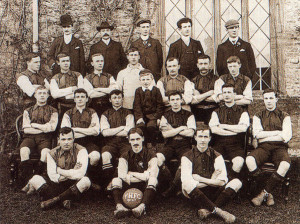

Even so, we often wondered how he earned enough (£4 10s a week when he died) to keep his family of nine children well fed and clothed. He even found time for a few hobbies – cricket, football and fishing -and frequendy went out early with his rod to the River Yeo. Upon his return he’d show off his catch (if there was any) to mother and charge his offspring widi laziness for staying in bed instead of enjoying the early morning fresh air. He would take his fish to the office and exhibit his catch to his colleagues, but by that time the fish had become ever more limp!

One of his habits which provoked great annoyance to mother was taking snuff, and with the vast number of snuff boxes which she found and emptied out of the window to the neighbouring churchyard, one wonders whether the vicar frequendy suffered from intense fits of sneezing!

As secretary of the Fire Brigade he didn’t need to go to fires, but never failed to do so whenever possible. A bell in the hall would ring and he’d rush to dress in his uniform and run to the nearby station with the other members, arriving by what means were available to them – general-

ly bicycle. If it happened during the night he often found it difficult to discover the whereabouts of pieces of his equipment, and in a very loud voice would blame members of his family of misplacing them while we’d been playing fire engines on our huge rocking horse. At the end of the farm fires he was happy to share with the others a reward of the locally-brewed Somerset cider or other refreshment of a similar nature.

Father was very adventurous. Once he drove to a country vicarage in a horse-drawn trap without any previous experience of such a mode of transport. Unfortunately, while he was in the vicarage transacting the business, the horse managed to slip its harness and found its own way home. Needless to say there was great concern when the horse arrived at its stable and it was thought that father had been injured in an accident. I’m not sure how he got home.

On another occasion he showed mother a

piece of paper proving that he had flown in an aeroplane from the local Westland’s airfield and twice looped the loop. Mother was both cross and horrified, saying she could have been left a widow with all the family to bring up if the plane had crashed: in those days aeroplanes were much less technically perfect in their construction, and even with skilled pilot one felt that the passengers took their lives in their hands.

My father had a lovely voice, and earlier had been in the choir of St. John’s Church, Yeovil. He was also an extrovert and with his banjo had belonged to a local Black and White Minstrel group which gave concerts for good causes. At our children’s parties he would sing, play his banjo and act appropriately all at once. He sang a song of the flea, and by some means would frequently scratch himself to make it more realistic. He also had a favourite laughing policeman song.

He was strict with his children, who had to be in by 10pm otherwise he’d lock up the house. Even when my sister was engaged and her poor future husband patiently waited around for her in the evening until she’d finished with the shorthand pupils she taught privately at our house, he’d hear my father saying sarcastically: “Bess (my mother), do give the poor boy a slice of bread and jam!” Although this would be said at about 9.30pm it was almost time for his departure. Although he was about 23 at the time, none of the family was expected to marry until at least the age of 25. On one occasion I was sitting next to my boyfriend at a local opera performance when I felt something tapping my shoulder; it was my father’s bowler hat and he was leaning over two rows of seats to remind me that it was time to be home. How small I felt.

Father was, however, generous, and sometimes on a Sunday he’d decide to take mother and us three youngest children to Weymouth. One rather cold Easter Monday he reached a similar decision, but after we got there brother Kenneth fell into a little pool between the rocks at the Nothe and got soaked. The other brother, Dennis, and I were told to take off some of our garments to help cover him and his clothes were stripped off and spread on the rocks in the hope that they’d dry. After a while father said it was a waste of time for him to hang around as well, so he took me off with him for a walk. However the walk turned out to be a football match at Portland which, as a little girl with no sporting interests, I didn’t enjoy at all. It wasn’t a warm day, so the state of mother when we got back can be imagined, as she’d remained sitting in the same spot for hours watching the two boys and clothes. She expressed her feelings very clearly!

Upon finding a stall still open on the beach on our way to the station we were able to get mother a cup of tea, but on the train home we young ones began to feel the pangs of hunger and it was then discovered that the leather case containing the remaining sandwiches had been left at the tea stall on the beach. What a day!

Father liked to wear a buttonhole whenever possible and if he couldn’t find a suitable flower in our small garden he’d select one from a neighbour’s garden as he passed by. No-one raised an objection, though, for with his kindness and humour, he was held in affection by all.

It was necessary in his work to prepare hand-written documents – especially for wills -and he could carry this out in any one of about six different scripts. A friend who worked in the local Post Office was told by an official, at the time of father’s death: “There goes the best writer in town.”

Kathleen Hawkins