Before the Second World War my two brothers and I lived in London but were lucky enough to have relatives at Skegness. My uncle kept a wet-fish shop there, and during the summer holidays my mother took us to stay. In the mornings she worked as a cashier in the shop, where it was not considered hygienic for a shop assistant to handle notes and coins as well as the raw fish. We three boys were left to amuse ourselves.

Before the Second World War my two brothers and I lived in London but were lucky enough to have relatives at Skegness. My uncle kept a wet-fish shop there, and during the summer holidays my mother took us to stay. In the mornings she worked as a cashier in the shop, where it was not considered hygienic for a shop assistant to handle notes and coins as well as the raw fish. We three boys were left to amuse ourselves.

Even in the early 1930s it was obvious that the sea was abandoning Skeggy. South Parade, the road that had once

fronted the sea, still had the eight-foot drop to what was once the beach, but now the sand had been replaced by lawns and gardens. Even further out was the vast boating lake, and only beyond that did the beach begin.

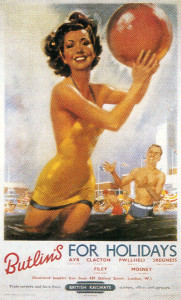

Along the sea front ran the ancient charabancs with their bench seats stretching the width of the vehicles. It cost a penny to ride from the Clock Tower all the way to Uncle Arthur’s, the amusement park opposite the Derbyshire Miners’ Home at the north end of the sands. We didn’t think Uncle Arthur’s was a patch on Butlin’s bigger, brighter amusement park back down the beach, seaward of the Clock Tower. Butlin’s Big Dipper was higher, faster and noisier than Uncle Arthur’s and day and night a clown, in coloured lights, bounced a ball, also in lights, across the front of the park.

In those pre-war days the sea still reached Skegness pier. Admission for children was a penny, although I remember one year, as an advertising gimmick, you could go on free by showing your Ovaltineys badge.

There was another way on, much more exciting, during the year they were

repairing the decking. By scrambling up the ironwork and along the supports over the sea, a boy could pop up through a hole in the planking half-way along – all free. On the pier were the penny-in-the-slot machines with such names as ‘The Allwin’ – which usually meant the ‘All Lose’ – and models in glass cases of things like prison buildings where a penny would open the big doors to show a prisoner surrounded by officials including the Governor and a Parson. A figure of a warder moved a lever and the prisoner, with a noose around his neck, dropped through the trap-door which opened beneath his feet. It was all over in a few seconds!

At the very end of the pier was a tall lattice tower with diving boards. At high tide times, as shown on the wooden clock face on the notice Leslie, a man who had lost a hand in an accident, drew crowds by performing spectacular dives. His swallow dives, half and full twists and back and front somersaults kept the spectators applauding as he climbed the ladder from the sea back to the top of his tower. He constantly reminded his audience that “..some of my young ladies will pass among you with a collecting box. Don’t forget the diver. Every penny makes the water warmer.”

Along part of the boating lake was an artificial cliff. There was a passage through, ‘The Axenstrasse’, with openings over the lake and a promenade at the top. This ‘cliff’ was one of my favourite climbs. Some ten years ago, to the embarrassment of my wife and the surprise of a couple walking along the top, I climbed it again. They didn’t expect to see an old gentleman, well into his sixties, appear over the edge of the cliff, artificial or not.

Happy days! Good Old Skeggy!

Bill Hathaway