They could be said to have served in the secret underground movement, but not in the sense most of us might imagine.

Many people today won’t have beard of the term ‘Bevin Boy’, but from December 1943 until the end of the war, no fewer than 47,859 Bevin Boys, named after wartime Minister of Labour Ernest Bevin, were directed to work underground in the coal mines.

The unpopular decision became necessary to meet production demands which were vital to the war effort, and in order to do this an extra 50,000 men would have to be conscripted over a period of 18 months.

The system employed by the Minister was that of a ballot scheme whereby young men of call-up age, upon registering, would be selected according to the last digit of his registration number. Draws were made every fortnight by the Minister’s Secretary. Even completing preservice training in a cadet force was not considered grounds for exemption.

Not all Bevin Boys were ballo-tees, as unballoted were given the opportunity, at the time of call-up, of choosing this form of employment in lieu of service in the armed forces, and were classified as optants or volunteers. They were not conscientious objectors.

After medical examinations, travel warrants and instructions would follow, those involved having to report to one of 13 Government Training Centre Collieries in the United Kingdom.

When they arrived at the assigned destinations, they would be greeted by Ministry of Labour officials who would allocate accommodation in either a miners’ hostel similar to an army camp, or in private billets, the cost of 25 shillings per week

being deducted from an average wage of £310s Od.

The training, which lasted four weeks, involved physical training, classroom sessions, surface and undergroundwork.

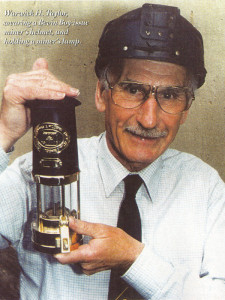

Bevin Boys were each supplied with a safety helmet, a pair of overalls and steel-capped boots. Like other miners, they each carried a safety lamp, a snap tin containing sandwiches and a water bottle.

After the initial training period, allocation would be made to work at a colliery usually within the same area where the training had taken place, and once more accommodation would be either in a hostel or private billets.

All Bevin Boys worked underground and were usually employed on conveyor belts or the loading and haulage of tubs

using machinery or pit ponies.

The work was hard, often in appalling conditions in cramped spaces, and entailed walking for considerable distances from the pit bottom over uneven terrain in areas that were hot, cold, wet, draughty, dirty, dusty or smelly. The constant noise of machinery was deafening, coupled with the daily hazards of cuts, bruises and the ever-pre-sent risk of explosion and fire caused by ‘firedamp’, methane gas or rock falls. There were no toilet facilities.

Some of the larger collieries were lucky enough to have pithead baths where workers could have a shower and change into clean clothes, but where these were not provided it would mean going back to the hostel or billets to do this.

How did the Bevin Boys rate with fellow miners who were suddenly faced with an invasion of young, inexperienced men with little knowledge of the industry? It was understandable that a certain amount of suspicion fell upon these newcomers from all walks of life, many who had never even got their hands dirty before.

Regular miners, many of whom had been born and bred in a mining community, who relied on bonuses earned by hard work, would not relish the idea of working alongside a Bevin Boy who showed a complete lack of interest and did not pull his weight.

Fortunately these fears and suspicions were soon dispelled as the newcomers proved their capabilities.

The Bevin Boys did not have a uniform and therefore wore only civilian clothes when they were off duty. Small wonder that this attire attracted public attention prompting adverse remarks as to why they were not in forces’ uniform.

As they were of military age, they were often challenged by local police on suspicion of being draft-dodgers, deserters or even enemy agents!

With the ending of the war in Europe, eventually a release scheme was introduced similar to that of the forces, but Bevin Boys received no other form of recognition or reward for their services to the war effort, in which they played a vital part.

I served as a Bevin Boy in South Wales, and have never lost respect for the miner – but I’m determined that the role of the Bevin Boy will not be excluded from the history of the nation.

In recent years a National Bevin Boys’ Association has been formed. Current membership is more than 1,300, and we always welcome new members.

Warwick H. Taylor