“Come on,” said Mother. “The siren’s gone. Down to the shelter. “It was just before 10pm on the night of Good Friday, April 11 1941, and I couldn’t have been in bed for long.

Such disturbances had been a regular occurrence during the last few months, so down the garden we trundled – Mother, myself and brothers George (15) and Roy (13), I was the youngest, aged 11. We all had our allocated carrying duties, myself with a few pillows, my brothers with blankets and Mother following on with a box with all the important papers such as ration books, insurance policies, a few old photographs, birth and marriage certificates and anything important she could think of. Father was on nights at the aeroplane works at Patchway.

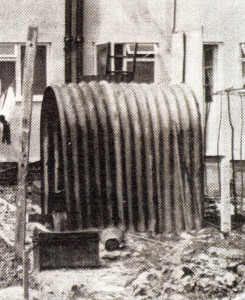

The Anderson shelter consisted of six pieces of very heavy gauge corrugated iron, each sheet about six feet tall and curving in at the top to form a tunnel shape. These were bolted together at the top with halfinch bolts with a front and back of the same material added. A front entrance consisted of a 2ft. by 3ft. gap. The whole lot was buried, to about half its height, and the earth extracted from the hole was placed on the top to protect it from bomb splinters. It was the householder’s responsibility to build a blast wall to cover the entrance. Ours consisted of a big box shape, some 2ft. thick, 4ft. wide and 6ft. high, also filled with earth from the garden.

The inside measurement of the shelter was 6ft. by 4ft. 6in., so you can see that it was a bit of a squeeze. One of the early faults with this type of shelter was that when it rained, they would partly fill with water, so quite few times I had to bail it out with a bucket. The council overcame this problem by concreting a three-inch shelf to the inside halfway up to ground level. This proved invaluable as a 6ft. by 2ft. frame was issued with wire mesh to make a bed frame. This rested on the concrete ledge with a bed made up, and was sufficient for us boys to try and get some sleep. Mother had an old armchair.

This particular Good Friday night brought one of the heaviest raids we’d had so far. I don’t think that any area of Bristol escaped that night. It was reported that 180 had been killed, 146 seriously injured and 236 slightly injured.

Life in the shelter was no picnic, especially in the winter when it was damp and cold. We used to wrap up in overcoats and lighting was by candle but there was no form of heating. All our bodies in such a confined space probably kept us a bit warmer.

The all-clear siren sounded at about 4am, so it was back to bed – no school this time as it was the Easter holidays. During the night we’d constantly hear bombs whistling overhead and land with a crunch, shaking the ground. The noisiest thing, and the one that frightened us the most, was the mobile bofors gun that seemed to stop up the street and let off a few rounds. I think the object was to keep these guns on the move rather than being on a fixed site that could be put out of action by the bombing.

I can’t say that we missed much schooling, although at times we must have looked half asleep. Discipline was more strict then, so we were expected to be alert at all times.

When the war started in September 1939 the Bristol area was deemed to be safe, so evacuation of the children was seen as unnecessary, although hundreds of children from the London area had been billeted in villages around the area. This was soon to change. Mother was sent a note from school saying that I was on the list for evacuation but that my two brothers, not being in the same age group, would not be required to go. I suppose it was like waiting for your conscription call-up papers (that was another phase of my life I had to go through at 18 years old).

My turn came in early May 1941. Off to school I went carrying a pillowcase and few belongings, my gas mask and a bag with cucumber sandwiches supposed to be for our dinner. Upon arrival at school we were issued with a big label to tie around our necks for identification purposes. We were now truly evacuees. There seemed to be hundreds there, and quite a lot of mums with young children. Double-decker buses were lined up along the street, one of which I eventually boarded. None of us had a clue where we’d land up. With another few bus loads, I was transported to Stapleton Road Station, Bristol to start my mystery journey. There were no mums or dads to see us off, but I can’t remember any kids crying at all -it was one big adventure.

Nowadays, whenever I go through the old station on the train, I remember hundreds of children swarming on the platform, which is still there, although now deserted.

The furthest I’d been on a train before was from Horfield Hall to Severn Beach, a journey of about 20 minutes costing 1/ld. For many of the evacuees it could possibly have been their first train ride. Eventually we were fully loaded and away. We all had visions of travelling to Wales or up North somewhere, but we soon had some idea as we travelled south through Bristol, making our first stop at Bridgwater, where a couple of carriages were emptied. We then went along the Minehead line stopping at various stations to disgorge a load of excited children. Our turn came when we got to Williton station, about 17 miles from Bridgwater and six from Minehead.

Charabancs were waiting outside the station to transport us to the surrounding villages. Ours went to Watchet, where we were duly set down at the local school awaiting our allocation to various houses. By now I had palled up with a lad called Barry Redwood and it was late afternoon. It didn’t appear that any child had been given a specific person to go with as the local residents just came in and selected whoever they took a fancy to. Barry and I were the last two left, so by then we were really down in the dumps. Eventually a lady came in with two little children in a pram and whisked Barry away with her.

It seemed there was nobody left for me, so out of the goodness of his heart Mr Young, the headmaster of the school, decided to take me until other arrangements could be made for a permanent place. Mr Young, his wife and two children -an 11-year-old boy and a 14-year-old girl -lived in a big house on the main road out of the town. His children went to Minehead Grammar School.

At Mr. Young’s I was given a room of my own. This had been unheard of at home, as I’d always slept with brother Roy. Being the headmaster’s house, it was quite posh. I had to wash my hands before meals and Mr. Young would say grace at the main evening meal. It was all very strange to me, and one thing I was never going to get used to was going to bed at 7pm, as back at home I’d been lucky to get to bed at all if there was a raid on. There was also church three times a day on a Sunday with the family.

My friend Barry landed up quite the opposite. The lady he was billeted with was on her own with the children. We pre-

sumed her husband was away in the Army, but we never did find out. He could do just what he pleased, and quite a few times he baby-sat while the good lady went out.

Our schooling was most haphazard. A Mr. and Mrs. Hayward, who had come down from Bristol, were our teachers, and they must have had a mammoth task. Our school was the Conservative Club room on the Esplanade, our classroom being made up of card tables and a large table tennis table. Can you imagine what it was like with about a dozen of us sitting around this table and four to each card table? I think there were about 25 of us, ranging from about seven years old to nearly 14, so the Haywards had their work cut out trying to drum some sense into us.

After I’d been at the headmaster’s house for about a week, the siren sounded for an air raid. As it did not normally go off in Watchet, the headmaster insisted that we all take shelter under the stairs. As it was the early hours of the morning we were all half asleep. It was like a little room under the stairs, so with a few chairs to sit on we waited with great expectation for something to happen. Sure enough, after a time, there was a whistle of a bomb coming down, but no thud or shake this time.

This started the headmaster’s children screaming. I don’t think the headmaster or his wife liked this as they, apparently, had not experienced an air raid before and it seemed that no air raid shelters had been provided.

As a veteran of the Bristol air raids, I just sat there and wondered what all the fuss was about. After a short time the all-clear sounded and we went back to bed. The attacker turned out to be an odd raider disposing of his bombs which had landed in the sea. Perhaps they were after the port-who knows? It did have a thriving coal and timber business.

After about two weeks I moved to another billet and I cannot say I was sorry as, although they treated me very kindly, their middle-class background was not the same

as I’d been used to. Now, at 69, I have a different view of the class society.

After saying goodbye to the headmaster and his family, I was taken to stay with a Mr. and Mrs. Stacey, the village postman and his wife. They had no children and lived on a small council estate on the edge of town. This was more like it! I had much more freedom and no more church on Sunday, although the Youngs did expect me to go. I could even go to the pictures at the end of the Esplanade. I could go around to my pal’s billet in the evening and get back at about 10pm. Barry was usually baby-sitting. I often wondered why the postman would give me a couple of shillings to go out. Never mind – it was very acceptable!

There were no visits from Mum or Dad, but plenty of letters and the occasional parcel with some goodies in and perhaps a postal order for 5/-. I often went over to the dock area on my own. There seemed to be no security and I often thought that the Germans could land there easily. No doubt there were checks that I couldn’t see. I used to talk to the sailors, quite a few of whom came over from Cardiff with cargoes of coal.

There was a gun site at Donniford a couple of miles from Watchet, and it seemed that every day they were shooting at something. Eventually I discovered that their target was a big red drogue being towed behind an aircraft out in the channel. There was quite a distance between the plane and the target for obvious reasons. They must have made a hit now and again as big pieces of red canvas were washed up on the shore now and again.

I was getting homesick by now. This country life was not for me, so every time I wrote home I’d say: “Come and get me.” Eventually, after a few months, Mother relented and back home I went. Thus ended my spell of evacuation. Quite a few children stayed until the end of the war, then got jobs and stayed on.

MRudge