It was 1943. A 14-year-old lad, rather small for his age, had moved to Lincolnshire where, it seemed, the whole world was covered in potatoes and airfields.

It was 1943. A 14-year-old lad, rather small for his age, had moved to Lincolnshire where, it seemed, the whole world was covered in potatoes and airfields.

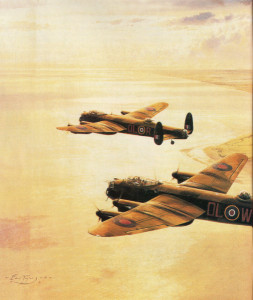

The airfields, or rather the humming Lancaster bombers that constantly took off from, or landed in them, were of much more interest to a lad than were potatoes. He spent his time out of school, and sometimes in school too, looking up at the sky. It was the ambition of every boy in his class to fly a Lancaster.

Those that had power over him, however, decreed that it was potatoes that he should concern himself with. There was a war on, and England needed food. The boys of his new school were ordered to help with the potato harvest. Oh Joy – a week off school!

Our boy turned up at the appointed time. It was early morning, and cold and damp. He had on his short trousers, only recently discarded on reaching the magic age of fourteen. His short trousers were definitely a backward step, and there had been a battle at home, but Mother said there was no question of his wearing ‘longuns’ – and that was that.

At least he had on a warm pullover, and a balaclava. One or two of the boys only possessed one pullover, and that must be kept for best, so they had their mother’s woollen scarf wrapped about them, fastened with a safety pin at the back.

It was hard work. The spinner raised the potatoes to the surface, and the boy picked them up and put them into large, wicker baskets, to be heaved by adults to the waiting cart.

Before long, our boy’s back ached, so he progressed through the damp field on his knees. His back stopped aching, but his lower legs were sore and scratched.

There were breaks in the toil. The farmer’s wife brought round hot tea during the morning. Then, at twelve, the children sat on waterproof sheets by the hedge bottom, to eat their lunch. There was home-made bread and damson jam, together with a little fat bacon, all wrapped in grease-

proof and brown paper. Most Lincolnshire families kept a pig in the back garden, so bacon -scarce to others – came in plenty.

Then there were the illicit breaks to watch the Lancasters circling. They were tested

locally after repair to damage caused by enemy action.

In mid-afternoon work ceased, and the bovs lined up for their pay. Sixpence an hour was the going rate, so three shillings was the prize for the day. Our boy clutched it tightly – a half crown and a sixpence. Alas, though, it was not his to spend. Every penny must be taken home to mother for new shoes were needed for the younger children.

But what pride he felt at contributing. And what a fuss was made of him in die evening. He sat closest to the fire, in a chair with arms next to his father.

His sore legs were forgotten as he told his admiring brothers and sisters about the day.

I know – that boy was me!.

B. E. Rudkin