Britain was slowly recovering from the Depression and mass unemployment; Hitler had just come to power; Arsenal were League Champions; and England won the Ashes in the infamous ‘Bodyline’ series.

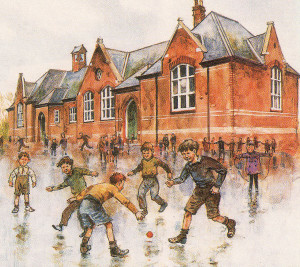

It was 1933 and, in a small Victorian brick and slate building, my schooldays were just beginning. The school had only three classrooms, each with an open fireplace and, on one side of the playground, stood a row of wooden lavatories, screened by a close-boarded fence. The school roll numbered about 100 and there were three teachers in addition to the Headmistress.

We were fed a strict diet of the three R’s; endless chanting of tables until we knew them backwards; expressing fractions as decimals and vice-versa; percentages; spelling; compositions; and when we weren’t reading ourselves, the Head read Dickens and Jack London to us from her dais in the corner.

Not that other subjects were neglected. In those days, teachers were expected to include history, geography and nature study in their repertoire while our senior mistress also taught needlework, country dancing and PT.

She ran the girls’ netball team and, as there were no male staff, the boys’ football team as well. All this on a salary of £195 per annum!

A Geordie by birth, she had a great interest in soccer and, in 1938, took a party of us to see our first professional match at Brentford (who lost to Liverpool 1-3) at her own expense.

The headmistress, a strict disciplinarian and brilliant academic, also displayed her generosity by ‘treating’ two or three classes to a seaside outing every summer while cinema visits were annual events. At Christmas, she organised plays or concerts, performed on a makeshift stage -long planks supported by iron-framed double desks.

Lessons apart, we also learnt good manners and common courtesies. And we were taught to value our national heritage in those days of Royalty and Empire.

On the morning of Empire Day (the afternoon was always a holiday), we paraded in the playground, unashamedly singing patriotic songs, marching and flag-waving. Pupils were encouraged to bring a Union flag to school and many houses flew them from their windows. Additionally, we respected St. George’s, St. Andrew’s, St. David’s and St. Patrick’s Days in their turn.

Special events like King George V’s Silver Jubilee in 1935 and George V and Queen Elizabeth’s Coronation in 1937 were celebrated with great national pride as we enjoyed an extra three days holiday, tea parties and cinema visits. Everyone received a souvenir medal, mug and commemorative book.

The majority of pupils walked to school -some had a bus journey as well. Bicycles were a luxury few could afford. Those who lived nearby went home to lunch – the rest brought sandwiches. No canteens then! A ha’penny bottle of milk – one third pint -was available during morning break.

At breaktime, the playgrounds became hives of activity. Boys and girls were separated by a wire fence and no-one dared to cross the frontier.

The boys’ main pastime was football -played with a tennis ball but non-players found numerous other interests. ‘Fag’ cards, marbles, ‘five-stones’ conkers, ‘bung the barrel’ were all in evidence while a thriving trade existed in swapping anything from cigarette cards to ‘tuppeny bloods’ such as Hotspur, Wizard, Adventure and i&w^rcomics.

Back in the classroom, we had an annual inspection by H.M.Schools Inspector and regular visits from a lady dentist. A nurse examined pupils’ hair (rudely known as a ‘nit nurse’) and an Attendance Officer could easily strike fear into a few hearts – although truancy was rare.

On the road to school was a sweetshop called ‘The Bon Bon’. A shack-like, corrugated iron building, it housed a treasure-chest of goodies displayed invitingly under its glass counter-top. A ha’penny could purchase a sherbet fountain, liquorice pipe or bootlaces, ‘everlasting strip’ toffee, aniseed balls or gobstoppers – and prices started at a farthing. Only the poorest children -and unfortunately there were several – could pass the shop without buying something.

The school was extended in 1935, accommodating more pupils and staff. There were now six classrooms, but the outside toilets remained. By 1938, the pupils numbered 175 and, in September as war clouds gathered, they were all issued with gas masks. Later, a load of sand arrived with a solitary bucket and shovel – shades of Dad’s Army.

A year later, when war was declared, we were still on holiday. The summer term would be the last in peacetime for six years but, despite this sad ending to the decade, many of us would, in retrospect, consider our Thirties schooldays as among the happiest of our lives.,

James Skinner