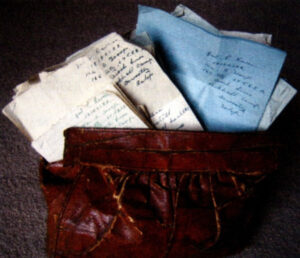

When my father died recently aged 82, I cleared out his council flat in London. I came across an old handbag which had belonged to my late mother who passed away a decade before. The bag contained no less than 70 love letters that my father had written to my mother while he was doing National Service in 1947.

Most of the letters begin with the phrase, ‘Just a few lines in answer to your most welcome letter…’ And they end with a mountain of kisses.

My father was 18 at the time and as well as the touching endearments and the expressions of deep emotion, his letters offer a fascinating insight into what it was like for him in an army camp far from home. They shed light on a short but memorable period in his life that he never talked about.

They’ve certainly inspired in me a keen interest in those traumatic post-war years when the young men of Britain were forced to join the armed forces.

My father, Patrick Raven, was born in 1929 and so he was one of thousands of young men who were conscripted into the army after the Second World War.

His call-up came shortly after he met my mother, Rene. He was sent to the Park Hall Camp at Oswestry in Shropshire and also spent a short time at a camp in Ireland. Like most of the ‘boy soldiers’ it was the first time he had been away from home and he was like a fish out of water.

He was homesick, bored and desperate to escape the monotony of camp life. In one letter his frustration was evident. ‘I’m going to talk to the commanding officer tomorrow to see if he will let me have a couple of days of compassionate leave. I’m going to spin a yarn, so keep your fingers crossed… I am properly browned off and I miss you a lot. It wouldn’t be so bad if we had something to do except lie on our beds and think…’

My father was lucky in that he had a girlfriend to write to. But others did not.

In a letter posted in August, 1947, he wrote, ‘I’ve been talking to my mate and he told me to ask you if you can get him a girl to write to, but he wants to see a photo first…”

The daily life of the conscripts consisted of field and rifle training, room and kit inspections, drills, marches and parades. They lived in barracks with little heating, poor washing facilities and awful food. They were paid very little and often went for months without any leave. Most of their social life was spent in the NAAFI where the boys could relax.

Here’s an extract from a letter my dad wrote in October 1947, ‘It’s been raining all day but we still had to do our five mile bash. We got soaked through and it nearly killed me… tomorrow we’ve got to do a mile with full pack on in so many minutes…’

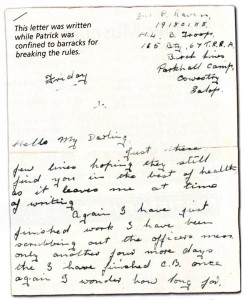

My father was not used to being disciplined and he and his mates were often punished for breaking the rules and consequently confined to barracks (CB). In many of his letters he mentioned being in trouble… ‘I’ve just finished another night of CB. This time they got me looking for worms for the Sergeant Major’s ducks… My mate has been put on a charge for hitting a Corporal. It looks like he will be joining me on CB… one of my mates has got seven days CB with me for having a dirty knife, fork and spoon – so you can see what it is like here… I got into camp late but I was let off lightly and only got seven days’ CB. I reckon it was worth it because I saw you and I was with you and that’s all I wanted because I’ve missed you so much…’

Entertainment for the lads was simple but well appreciated. ‘I’m going to the pictures tomorrow night in the camp to see The Way Ahead with David Niven. I’ve seen it before but I might as well see it again as there is nothing else to do… As I am writing this letter they are playing my favourite song, Guilty. Whenever I hear that song I think of you…’

Sometimes they had to make their own entertainment. ‘We had another pillow fight last night. One of the boys was knocked out and another one got a black eye. It’s a proper rough house once they start… I’ve just finished playing dice with the boys and won 25 bob so I am sending you a pound to get yourself something. If I keep it I will only lose it…’

Fit for pigs

The food was pretty awful by all accounts. In his letters my father frequently moaned about what was dished up. ‘We had stinky fish for tea tonight. It wasn’t fit for a pig so I am going to the NAAFI to have a few cakes… I have just come back from tea. It was useless. We had sweaty cheese and two slices of bread… Right now I’m gasping for a good cup of homemade tea.

When I come home, I will drink so much tea that I will probably begin to look like it.’

The recruits worked hard and sometimes the work could be dangerous. ‘We went in the gas chambers yesterday,’ my father wrote. ‘We had to take our gas masks off and just stand there. When it was time to come out we couldn’t open the door and couldn’t get our masks on again. It nearly killed us and a couple of the boys fainted.’

In another letter he said… ‘ I had an accident today. One of the boys sliced the top of my thumb off while he was on the gun. It’s a bit sore but it will be alright by the morning, so don’t start worrying. They’ve given me some sleeping tablets…’

My father’s letters are a treasure trove of anecdotes and information about a period of his life I knew nothing about. I’m sure that what he experienced during National Service helped shape his character and to turn him into the fine, upstanding man that he was.

I’m thankful that he kept the letters all these years and I’m determined that they’ll stay in our family for generations to come.

Jim Raven