The year of 1945 was a memorable one for me. Peace was declared, my father came home for good – not just on leave – and I went to school for the first time.

Whitefriars school stood in a little town called Wealdstone, near to where the built-up areas thinned out to the countryside of Hertfordshire. It was a red brick Victorian building with high windows and a tarmac playground surrounded by a barred fence. This was great fun to climb on or swing from at playtimes.

The infants, all 35 of us, were in a large high-raftered room. Green tiles around the walls reflected the changing light from the windows and at one end was an open fireplace where coals burned, warming the entire area.

We soon settled in and became accustomed to the rituals of our new life except, that is, for the toilet arrangements. Until we left to go to the ‘big’ school, they remained the bane of our young lives.

On top of the teacher’s desk stood two packs of toilet paper, renewed each morning by Mr Hurst, the elderly caretaker. Now the ruling was this. The hand went up, permission to go to the ‘lavatory’ was given and, under the eyes of 34 classmates, you collected the regulation two sheets and left the room.

Next came the dash across the windy playground to the wooden block of toilets, standing in solitary splendour in full view of most of the school. Four toilets under one roof, they were kept spotlessly clean by Mr Hurst and smelt only of damp wood and strong disinfectant. I have often wondered whether the knot-holes were deliberately left in the wood to discourage long sittings. The draughts were incredible. The greatest hazard, however, was at playtime when those knots served as peepholes for the rest of the school. It was a hardened or desperate pupil who risked such embarrassment at these times.

I had been at school for about eight weeks when news came that my father was to demobbed. I remember wondering what that word meant but decided that it couldn’t be anything too bad because my mother was so happy. Gradually the atmosphere began to affect me. I couldn’t wait to see him either. There was a picture of him on the sideboard dressed in khaki and I sat in the evenings looking at it, wondering what he would be like. He had, after all, been away for most of my life.

Dad was due home on a Friday and mother kept me off school.

All day I sat at the top of the stairs waiting for the door bell to go. My mother was even more excited and kept going backwards and forwards to the front gate to see if he was coming.

Eventually the bell rang, mother opened the door and he stood there, looking up at me and smiling. Just like his photograph. I threw myself down the stairs but missed my footing and landed at his feet with a thump. It turned out that I had dislocated my shoulder. My poor father, I don’t know who was more upset. What a homecoming!

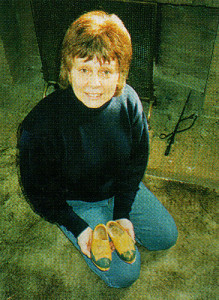

From Holland, he had brought me a little pair of clogs, brightly painted in red, blue and yellow with my name on the front. They fitted perfectly and, when my arm healed and I took them to school, I was the envy of my schoolfriends. I have them still, next to that photograph of my father,

Ann Priest