Every time my wife insists on me sharing the household chores (I readily admit I am a reluctant volunteer) I gently remind her about Zebo, the black-lead cleaner, and what life was like for her mother in Caroline Place, Aberdeen, in the 1930s.

It’s all contained in her mother’s old recipe book entitled The Science of Homemaking by Kate Kennedy, who was a lecturer and demonstrator in domestic subjects at Glasgow Provincial Training College.

The book is divided into three parts -Cookery, Laundry Work and Housewifery, and was designed to meet the needs of teachers and pupils in all post-primary departments of Scottish and English day schools.

In Part 1 the advantages of the modern gas cooker over the open range, closed range or combinadon grate is demonstrated, but it was more likely that the average non-working housewife of the

1930s possessed the latter stove for her cooking. It meant that she rose early to clean it before breakfast. Her first mucky daily chore entailed removing the cinders and ashes (reserving the cinders for burning in the refuse pail in the evening together with vegetable, fruit and other food refuse subject to decay) and raking out the soot from the flues, under the boiler and round the oven. Brooke’s Soap or Thomson’s All-Round Cleaner were recommended to remove stains from the inside of the oven.

The top of the range had to be rubbed with paper to remove any grease, and then there was the tricky part of laying the fire, in such a way that there was plenty of air admitted – an art in itself! Finally she had to brush the hearth-stone and black-lead all the iron parts (and they were considerable!).

This is where Zebo, a liquid form of black-lead, came in. The other cleaners used were Cake, to be mixed into a paste with water, and Enameline, which was already in paste form. The iron parts were then polished with brushes and finished off with a velvet pad.

A thorough washing of the hands was necessary before preparing breakfast. I wonder how many husbands commented on the small black specks in their porridge before leaving for work? I suspect it was probably more than their lives were worth!

My wife usually skips through Part 2, as she has no illusions about pre-war laundry work. There were no washing machines with their pre-set programmes in those days, only indmidating boilers, strong soda and washing powders, guaranteed to roughen the most delicate hands. The soiled clothing had to be rubbed with soap and soaked overnight in cold, salty water. She wouldn’t be overjoyed at this or at starching my shirt collars and cuffs for work, but I could see her operating a mangle with gay abandon, hoping to catch one of my fingers in the rollers, as I folded the articles to push through.

I tease her about what makes the best cleaning agent for silver in Part 3. According to Kate Kennedy, it was Precipitated Whiting. I can visualise her mother suspending a small piece of Whiting in muslin in a large jug of cold water overnight, pouring off the clear water in the morning and then drying the milky substance left in a slow oven. Apparently the end product is an excellent cleaning agent for the best silver.

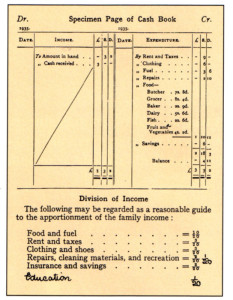

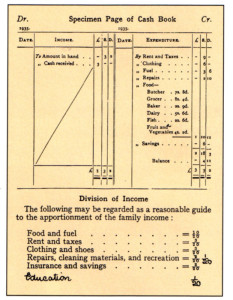

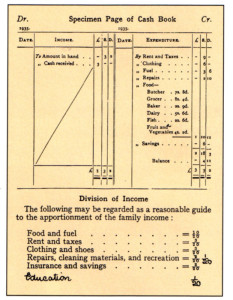

Finally, apart from everything else, the 1930s housewife was expected to be a mini Chancellor of the Exchequer. She had to account for all household expenses and keep a division of her income in a cash book (note the recommended guide to the apportionment of the family income in the example attached circa 1935 and how her mother, quite righdy, had added EDUCATION to the list).

So would you rather have been male or female in those days? It’s something to contemplate as I put on the Marigolds to wash up the breakfast things…

David Shotifield