David Sansom of Royston, Hertfordshire remembers:

Thirty five pounds plus an old motorcycle, that’s what it cost me to progress from two wheels to four when I bought my first car in the summer of 1962.

I traded in my somewhat tatty, and well past its prime, Excelsior Talisman Twin for an equally well used, scruffy Hillman Husky Estate.

Ah, happy days. There was always a willing and knowledgeable friend to show you how to grind in the valves, set the correct gap on your spark plugs and to lend you a set of axle stands when the brake pads needed changing.

Today, if you’re brave enough to lift the bonnet of your new car what do you find? A swathe of dark gray plastic, through which protrudes the dipstick enabling the oil level to be checked. One of the few other accessible items is the windscreen washer bottle which can be topped up by the driver; not forgetting of course the anti-freeze mixture – all as instructed in a helpfully illustrated 200 page owner’s manual!

Anti-freeze in the radiator? My clever friend forgot to mention that and when the ‘big freeze’ arrived in the winter of 1962/63 the engine of my beloved Husky froze solid. (I will refrain from comment as to the unfortunate choice of name for this car under the circumstances.) There it sat forlornly outside my house in northwest London for more than two months, unused and with a permanent coating of snow and then ice.

I was warned, again by my friend who knew about these matters, that’the block’ would crack and a replacement engine would be the only recourse. He was wrong. The thaw came at last and being of an optimistic nature I unlocked the car, perched myself on the cold, unyielding vinyl seat and turned the key to start the engine. It purred into life, well perhaps not purred to be honest, more sort of rattled, but it did start.

The Hillman motored on for another year or so before the time finally came to replace it with a more advanced piece of machinery. Ultimately, the £601 had set aside proved to be insufficient to acquire the latest in automotive technology, even 50 years ago and thus my second purchase was a 1950s’upright’ Popular 103E, a relic of Ford’s pre-war motoring catalogue.

The highlight of this car was, without a doubt, the vast amount of leg room, almost of limousine proportions, in the back seats. Everything else about it was basic in the extreme, including the three-speed gearbox and, worst of all, the solitary windscreen wiper. This feature was guaranteed to induce high stress levels when travelling up a hill in heavy rain as it was operated by a vacuum system off the engine; as the car slowed so did the wiper blade, ever so slowly traversing its arc mesmerically in front of you. Going downhill was equally alarming; the light load on the engine allowing the wiper arm to thrash crazily from side to side at high speed.

I had disposed of the Hillman by selling it to a scrap metal merchant and in my youthful ignorance had assumed that having collected the princely sum of £2 in cash from him that would be the last I would hear of the car. It never occurred to me that I had to fill in any forms confirming the transaction.

Imagine my surprise when one day a few months later a policeman knocked on the door of our home and enquired if I was the owner of the Hillman Husky. I explained the circumstances of my selling the car to which he responded that it had been spotted down in Devon travelling at, as he put it,”an excessive speed”.

I suggested to the officer that bearing in mind the condition of the car when I had last driven it I found it surprising that it had got as far as the West Country, let alone at high speed. There must have been an element of doubt as to the identity of the vehicle as he appeared totally satisfied with my explanation, apologised for bothering me and went on his way.

But to return to the Ford Popular; eight months and two enjoyable, relatively trouble-free motoring holidays later the ‘Pop’decided one morning to expire completely on my way to work. One quick phone call to a local car breaker and the Ford was destined to make its final journey

to end its days among its similarly cast-off brethren in a cluttered, oil-soaked yard somewhere in west London.

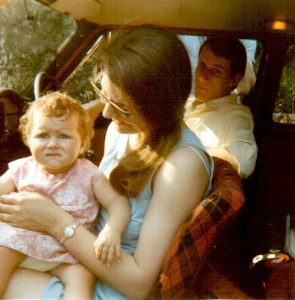

After the demise of the Popular I was more than happy to go back to riding motorbikes until, that is, my wife-to-be and I came off the bike just two weeks before our marriage in September 1967; despite being unhurt we began to ponder on the benefits of returning to the relative safety of four wheels. Then, in the spring of 1970, came the confirmation that we two were soon to become three.

No question now as to whether or not we should acquire another car. And so I bought an old Austin A40 Countryman, this time a product of the early-1960s.

Looking back, I think that was the last car I owned which I worked on myself. Did I get lazy, too busy with my growing family or was technology already starting to overwhelm me? By the way, I was wrong about the instruction manual for our latest car, it actually has 400 pages and yet nowhere does it tell you how to grind in the valves – how ridiculous.

If the spectacle was not drama enough then consider the sounds. A mixture of throbbing motors twinned with those engines croaking in their death throes as steam whistled from fractured radiator hoses. There would be a clanking thud of metal against metal and writhing exhaust pipes would graze the tarmac to produce a galaxy of sparks.

Unbelievably some folk were able to determine a sense of order from the hurly burly. The rank and file stock car fans with clipboards and pens would write the results and times into their race programmes. Thirty-five cars may have started each race but only about ten would ever finish. Under the watchful eyes of their forlorn drivers the vanquished vehicles would be unceremoniously towed from the track by an army of breakdown trucks. Having seemingly exhaled their final exhaust these vehicles would vanish through the pit gates only to miraculously reappear for the consolation race, spruced up and back firing on all cylinders.

Chick Henson was one of the gladiators of

those halcyon days. He lived near a race track in Northamptonshire and easily got sucked to the sport. His first car cost £50 but these days a stock car would damage your pocket to the tune of £8,000. Alas,

West Ham was not one of Chick’s favourite tracks; he never did too well there, preferring the more intimate Harringay Stadium nearby.

West Ham Stadium – or Custom House as it was popularly known – sat, as the name suggests, in the heart of East London’s docklands. Designed by ubiquitous Scottish architect Archibald Leitch and built in 1928 it was a fitting citadel to the legions of stock car worshippers that passed week after week through its turnstiles.

In 1927,16 of the 22 football clubs of England’s top flight league had, at one time or another, been clients of Leitch.

A trade mark of his designs involved balustrades of criss-cross steel at the front of the upper tier of the double decker stands. The football stadiums of Liverpool, Fulham, Aston Villa, Wolverhampton

Wanderers and Tottenham Hotspur were all conceived from Leitch’s drawing board. When, in 1966, England hosted football’s World Cup, six of the eight grounds used had received input from this industrious Scottish architect.

West Ham Stadium did not host the eponymous football team though and was the only stadium designed by Leitch as a venue specifically for greyhound racing and speedway. An astonishing 83,000 people once jammed into the place for an international speedway match.

Stock cars debuted there in 1954, with a reported crowd of 45,000, and featured regularly until 1966. Greyhound racing and speedway continued until 1972 when the turnstiles clicked, rotated and locked shut for the final time.

Exiting the stadium at the end of a pulsating nights racing inevitably involved trudging through a two inch layer of discarded peanut shells. It must have kept the stadium cleaners busy for hours.