When I left home for university in 1951, with the prospect of two years’ National Service to follow, my mother probably thought I’d have no further use for the few personal belongings I’d accumulated as a teenager, including Ian Allan’s ‘ABC’ train-spotting books, Exeter City football programmes and the autographs I’d managed to obtain by standing outside the players’ entrance after matches. That she’d binned them in my absence caused me no great concern, for I had added to my interests and was about to get married.

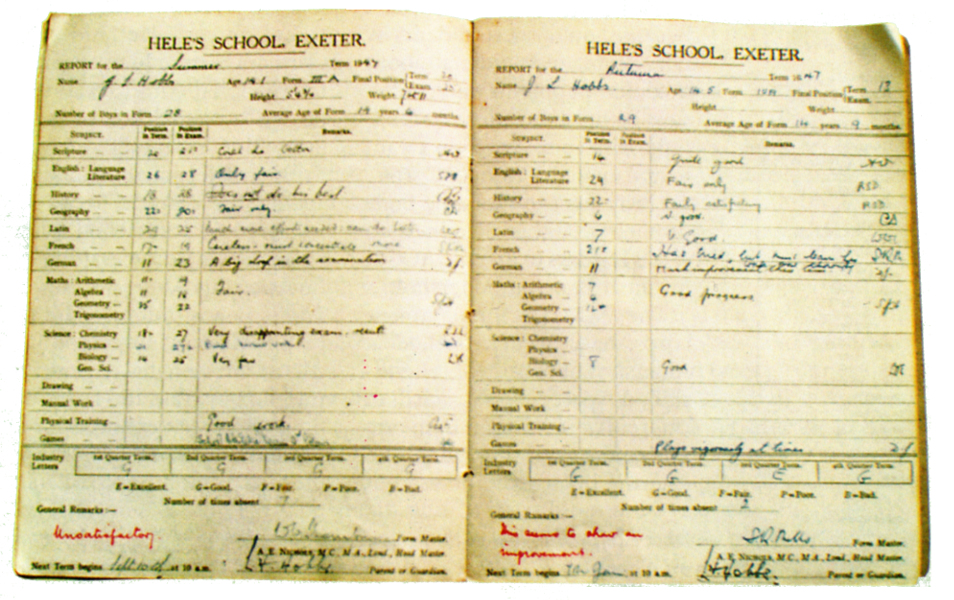

As time went by, though, I began wishing I still had the memorabilia of those formative years, and questioned Mother more than once in the hope that something might have survived – but to no avail. Then during one visit to us she sprang a total surprise by producing my book of reports from my six years at Hele’s School, Exeter – a grammar school. Although this wasn’t exactly what I’d been looking for, what a delight it was to see that book once again, for recorded between its green covers was a potted history of those very important years of my life.

Staying with us at the time were our eldest daughter, her husband and their three children, and as might be imagined they were fascinated by what the reports told them about my schooldays. The conversations that followed these revelations were most interesting, particularly as we learned for the first time that our daughter had actually amended her reports to her

advantage by – and it was just one example – converting a rating of B- to B+ by one very simple stroke of the pen! There seemed to have been no ‘audit’ undertaken when the report, signed by myself, was returned to school at the start of the next term, so she knew the risk of such forgeries being discovered was minimal.

That wouldn’t have been possible when I was at Hele’s School, for we were given a numerical position in the form for each subject, based on the various marks given for work undertaken in school or at home during the term. Thus in my first term at the school I was third in biology – “V. Good Indeed” and 19th – “Very Keen” – in French. Each term was divided into four, for which we were given industry letters ran-ing from E (Excellent) through F (Fair) to B (Bad), and those were also recorded in the report.

Each teacher registered my position and his or her supporting comments, and the headmaster added his ‘General Remarks’ which, for that first term, were “Splendid!”. I was delighted to take the report home to my parents, who were also provided with some relevant statistics within it. For example, the average age of the form was 1 lyrs 9 mths (I was 11.6), my height was 4ft 8ins and my weight 5st 71b. There were 33 boys in the form and my final position was tenth. Father was glad to sign the report,

and I returned it to the school at the beginning of the spring term which started on January 10 1945 at 10am.

Each entry made was initialled by the teacher concerned, and my family was quite surprised at the ease with which I still recalled their names – and their almost inevitable nicknames. Of course the teachers knew them too, but we pupils didn’t know that until reference was made during, say, a farewell speech at the end of a normally sad morning assembly – the devil you knew was better than the one you didn’t! Thus Mr. C. H. Bishop, to us ‘Bunny’, let it be known that he was off to his burrow, while Mr. A. C. Toyne, our scripture teacher, was well aware that he was rather better known as ‘Holyjoe’!

So far I’ve concentrated on my first term’s report, but my daughter noticed that the rot had soon set in, because by the end of my second year I was 22nd out of 29 boys, and that the headmaster had decided this was “Not Satisfactory”. My daughter’s comments were enquiringly caustic, as had been my father’s when I gave him the report back in the July of 1946. Always perceptive, he was not at all impressed with my performance. The only place where I could run for cover, and that was pretty thin, was behind the “Good” I received for physical training from Cecil Ford, one of the best outside halves never to play rugby for England, and who was later incapacitated by that dreadful plague of the time, polio.

In my third year the headmaster’s comments deteriorated from “Fair” through “Not Very Good” to “Unsatisfactory”. Although it was always great to have the holidays to look forward to, that end-of-term feeling of pleasure was more than a little undermined by the thought of the reception I would get from Father! His evening homecoming was feared, and I can remember the questioning and the lecture with no difficulty at all! When I could get a word in, I highlighted the term “Very Fair”, and was reminded immediately that this was worse than fair, which itself was less than good. In fact my form master told me that Father was wrong about the qualification of “Fair”, but that failed to do my cause a great deal of good, particularly as by then the new term had started, and I’d been reminded that better – much better – things were expected of me.

Somehow I managed to get a grip of myself during the fourth year, and during the fifth the headmaster found it appropriate to use the word “Excellent” with which to conclude the report for the spring term. That said, my daughter pointed out that at the end of my first year in the sixth form my history master had commented: “Quite good, though I feel he could do better if he made his maximum effort!”, while another, who taught economics and British constitution, wrote: “He has ability, and I am always waiting to find his work rather better than it is.”

So ended the written record of my schooldays. For me the book of reports had unlocked lasting memories of something of a roller-coaster ride in a school for which I have nothing but deep affection – and it was the very best of British schooling.

Our children and grandchildren love to open the pages of a book that is now an important part of the family’s archives, and thereafter chide me in particular about the two years or more of disaster that are recorded therein. How could I possibly be critical of them when I was so dreadful myself?

Only he who dares would argue with that logic!

John Hobbs