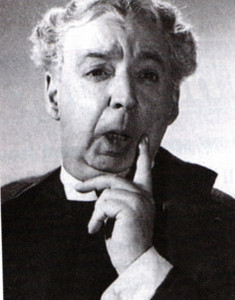

This film star may provoke head-scratching. You know the face… but the name? And his films (he made 125 of them)? But he didn’t take the lead in one film and mostly appeared in just one or two scenes as a bit-part actor – a warm, welcoming face. We knew instantly what the character was going to be like.

A permanent cherub

Miles Malleson’s beaming, cherubic face seemed a permanent fixture in British films (especially Ealing comedies and Hammer Horrors) in the 1950s; his trademark a bumbling, distracted demeanour, with perhaps an undercurrent of mischief. Typically he played a man of some small influence or importance but little professional aptitude, a bumbling doctor or bibulous clergyman.

He’s a practiced scene stealer, busying about in the background and distracting the audience from the star. When his character bursts into hearty laughter Malleson’s lemon-slice

smile seems to outgrow his face, his beady eyes disappearing.

If you do remember him, it’s most likely as Canon Chasuble in the 1952 The Importance of Being Earnest. A part he was born to play. Canon Chasuble was one of his biggest roles: usually he is a ‘speciality’ player, in a featured, one-scene role.

He appeared with Peter Sellers in Heavens Above and I’m All Right Jack, in Alastair Sim’s Scrooge, the Ealing comedies The Man in the White Suit and Kind Hearts and Coronets (as the philosophical hangman), in Train of Events (as the railway timekeeper obsessed with his

chickens) or in Michael I Powell’s shocker Peeping Tom (as a shifty old gent in a seedy newsagent to purchase some ‘views’).

In the late 1950s he became part of the Hammer Horror repertory company, where he was used to give the audiences some comic relief.

In the late 1950s he became part of the Hammer Horror repertory company, where he was used to give the audiences some comic relief.

My favourite Malleson appearance is as the Bishop in The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959). There is a splendid scene where he mistakes Peter Cushing’s Holmes for the technician who has come to repair his telescope.

He’s fond of a tipple, and prone to justifying the habit with Biblical quotations. He visits Baskerville Hall and keeps dropping the subject of sherry into the conversation: when a glass is finally offered he feigns surprise and affects a moment’s deliberation before succumbing.

It is almost impossible to imagine Malleson as anything other than an old man, but he had been in films since the early 1920s, and not just as an actor. Born in 1888 he was a highly regarded playwright and screenwriter, writing his first play in 1913 and serving as sole or chief writer on several famous British films, including The First of the Few (1942),

The Thief of Bagdad (1940), Sally In Our Alley with Gracie Fields (1931) and many of Anna Neagle’s most famous films, including Victoria the Great and Nell Gwyn.

Malleson was also an academic, noted for scholarly translations of Moliere. He was a close friend of Bertrand Russell, and an outspoken progressivist and pacifist in WWI. He sat on the council of the Masses Stage and Film Guild, established by the Labour party in 1929 to bring cultural works to the working classes.

A Cambridge graduate, he intended becoming a schoolteacher before succumbing to the lure of the stage. While still at university a politician failed to attend a dinner held in his honour. In a scene that could have been lifted from an Ealing comedy, Malleson pretended to be him, giving a well received speech while disguised by a fake white beard.

“1 would die with horror now,” Malleson claimed in a 1949 interview for Picturegoer magazine, “something of the spirit of adventure goes out of one!”

“The actor’s craft is founded on real interest in people,” he explained in the same interview. “There are two things to remember in creating a character: how a man looks and how he feels.” It is this simplicity that makes his characters, however exaggerated, seem so authentic and lovable.

“Sometimes it seems that drama is such a passing business,” he told Picturegoer. “A performance is given, a picture screened, then, probably, forgotten. Only occasionally do you hear that something is remembered…”

There is some irony, perhaps, that his enduring legacy is as a bit part actor. But 40 years after his death we only have to see him and we smile.

There are certainly worse ways to be remembered.

Matthew Coniam