My home duties of washing dishes, laying the tea table, and taking a duster to my bedroom were easy compared with the high maintenance of standards expected at school. The domestic science class had one aim – to prepare us for a future as dutiful housewives.

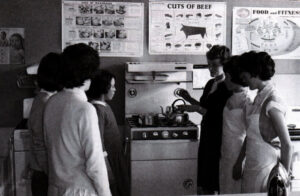

First we had to dress the part. Each week we were ordered by our teacher to roll up our sleeves, and don our hand-made gingham aprons and our triangular cotton scarves to tie back our hair. Armed with sweeping brushes, dustpans and polishing cloths, we marched in a crocodile line to the domestic science block.

Here several rooms were arranged in a manner which was meant to represent a typical 1950s’ home. The kitchen area displayed its modern day trends with the pristine earthenware sink and green, freestanding food storage cupboards. There was a gas cooker and a twin-tub washing machine, a luxury item compared with the hand turned mangle our mothers used at home. We also admired the blue and white china that stood on the Formica-topped table.

The bedroom was furnished with an oak-coloured wardrobe and a kidney-shaped dressing table with a mirror, a wicker chair and an ottoman. The bed had a top and bottom sheet, two woollen blankets, an eiderdown and was topped with

a candlewick bedspread. Our favourite room was the floral wallpapered living room with its modern beige-tiled, open coal fire hearth and complemented with a three-piece suite, a standard lamp and a Bakelite radio. The floor was covered with a large carpet square edged with linoleum.

Each week the class was divided into small groups and we took it in turns to work in the different rooms. We soon learned that housework was a laborious and serious business.

“This is all about elbow grease, girls,” the teacher informed us as we puffed and sweated as we went about our duties. Most of us worried more about suffering from rough red hands and housemaid’s knee in the same way our mothers did.

Not surprising, when we spent most of the time on our knees, brushing the carpet square, washing the skirting boards or struggling to spread the red cardinal polish on the linoleum floor and rub, rub, rub, until you could ‘see your face’ in the shine.

The teacher regularly cast a critical eye over our efforts and would often run the tips of her fingers over the ledges and window frames to make sure we had not left one speck of dust behind. Shirking was taboo and culprits were punished by being made to start all over again.

“Remember – your future husbands will expect to find their homes spotless when they return each evening from their hard day’s work.”

We were reminded of our fate constantly as we wrung our sheets of paper crumpled in vinegar and water to clean the windows until they gleamed.

Even while most of we 14-year-olds secretly pledged ourselves to a lifetime of spinsterhood, our lessons continued with the instruction to setting a dining table in preparation for the future husband’s evening meal. We soon learned that a good square meal on a table, set with well polished cutlery, was the only way we were likely to keep a man’s heart.

Even without realising our fate, we girls knew that we had been primed for housekeeping from the day we were born.

Most of us owned toy cookers and miniature household appliances. I’d spent hours of my childhood cooking plastic sausages and weighing ingredients in my imaginary kitchen. Or else, I’d sewed and ironed doll’s clothes in my make believe domestic scene. Not that we ever thought to question our role, of course. It was all because keeping the house spick and span is what our mothers did. That meant keeping a daily routine. And, ‘elbow grease, girls’ as I was taught all those years ago. sjjj*

Sally Bowler