My father Horace, Jim to his friends, began life in a barrel-topped gypsy caravan on September 6 1929, one of eight children born to Romany parents, Sidney and Mizzely Biddle.

Contrary to commonly-held romantic notions about clan gatherings and camp fires, life on the road was harsh. Of the offspring, only the daughter of the family, Nennie, was permitted to sleep in the caravan with her parents. The boys, Sidney Junior, Oliver, Jack, Wisdom, Frankie, Roland and my father were housed, for want of a better description, in a tent erected nearby. For reasons best known to my grandparents, they generally chose to lay down heir temporary roots next to a rubbish tip or river, and whatever advantage it held for them was far outweighed by the disadvantage of the catsized rats that visited the boys’ ‘bedroom’ each night.

As one of the eldest, Nennie became a substitute mother to each of the boys as they arrived while she was, in reality, little more than a child herself. My grandmother, meanwhile, had great success in conceiving and merely churned out one child after another.

All of the boys attended school at some time during their lives, but as they never settled in any one place for very long, no teacher considered it worth making the effort to educate them, although they did all become very adept at tending vegetable gardens! Needless to say most of the family were, and still are, illiterate, although Frankie and my father did manage to obtain a basic education during their obligatory two years’ National Service.

Nennie, albeit no threat to Agatha Christie, does write letters to my father even if she does spell words exactly as they are spoken, as her latest masterpiece addressed ‘Deer Orris’ quite clearly demonstrated.

Traditionally, feeding Romany children in the 1930s and 40s was seen as a waste of good hard-earned money, even though the hardships being endured throughout the whole of Britain during the wartime years barely touched their lives. Children were fed scraps of left-overs; they were to be seen

and not heard, but preferably not seen. Indeed, to be thrown a hunk of bread with the barked comment: “Get that down you, boy!” was the best the child could hope for, because in their own way the adults were actually showing a certain degree of affection by acknowledging the child’s existence. No Romany child ever refused such a generous offer.

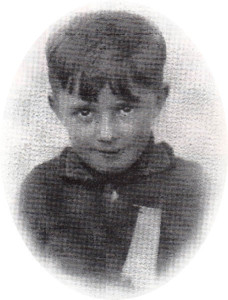

Adults and children alike were clothed out of the rag bag, and if the nearest fit happened to be a pair of army boots of a lady’s fur coat, it was perceived as serviceable clothing and would be worn, whatever the age or sex of the wearer. Consequently my father attended his first day at school, aged five, wearing an ill-fitting pair of girls’ buckle shoes.

Sadly, 1934 was not renowned as an era of tactful, kind and understanding teachers, and he was hauled out to the front of the class where he stood, head bowed, while she looked him up and down before speaking. To his horror and utter humiliation, she then appealed to the children to ask their parents whether they had any old shoes to spare which might fit “this poor little boy”. Now aged 70, my father still squirms with embarrassment at this vivid memory. Ironically, his parents were wealthy people compared to the sympathetic parents searching their cupboards for shoes to “help those less fortunate than themselves”.

At the beginning of the war my father was ten years old, classed as and expected to work like a man. The first job for all male family members at every new location was to dig an enormous trench and to construct something to hold a canvas awning. Upon completion of the task a wooden plank was balanced lengthways over the hole and, with the awning providing a degree of privacy, the little communal toilet was completed. It wasn’t very wise to use this facility while under the

influence of alcohol, for reasons best left to one’s imagination. As Romanies are not known for moderation or forethought, accidents happened regularly, and an all-over wash in the river on a frosty January evening was the quickest sobering-up process known to modern man. Customary, little-understood Romany rituals also included knocking each other senseless after an afternoon’s love affair with a barrel of beer and killing the previous night’s captured rats by throwing them into the fire. Neither activity was any more acceptable then any more than in today’s politically-correct age.

Despite the lack of education and literacy the family never failed to make a very comfortable living, utilising any talent they possessed, be it making pegs, mending umbrellas, selling lace and ‘lucky’ white heather, telling fortunes, dealing in scrap iron and manure, or simply taking advantage of the long-held superstition that it was unlucky to turn a gypsy away from your door.

In 1946, at the age of 17, my father’s life changed in a way he could never have imagined. He met and fell in love with my mother, the 14-year-old daughter of ordinary, working class, non-gypsy parents, and began a five-year courtship culminating in their much-opposed (by both families) marriage. My own birth in 1955 was in total contrast to my father’s, and took place in the relative comfort of the bedroom in their Birmingham maisonette.

Being half-Romany, or mongrel according to my mother, I grew up with all the advantages my father was never given the opportunity to sample. I enjoyed a full-time education from the age of five, went to grammar school and college, and have never had the ‘pleasure’ of balancing on a plank in a draughty communal toilet.

My father has seen more changes in the past 70 years than many of us could even imagine,

Sally Jobsott