Jane died when I was just 17. It didn’t come as a complete shock, and was only to be expected. She was an old lady and was considered to have had a very good innings. She had lived with us as part of the family since I was two years old, so I could barely remember life without her. We waded some very troubled waters together. She was like a sister, best friend and confidant all rolled into one.

Jane died when I was just 17. It didn’t come as a complete shock, and was only to be expected. She was an old lady and was considered to have had a very good innings. She had lived with us as part of the family since I was two years old, so I could barely remember life without her. We waded some very troubled waters together. She was like a sister, best friend and confidant all rolled into one.

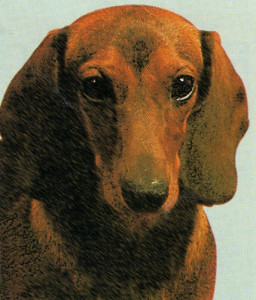

She was a rather roly little creature all round really. Dachshunds at their finest are slim and sleek and proud, yet I remember her best when she was so fat her belly grazed the ground when she walked. Her lovely brown eyes were only metaphorically bigger than her belly. This state of affairs couldn’t have lasted. When she was about eight years old it was discovered that she had a heart murmur, and she was dieted down to delectable trimness. This undoubtedly added years on to her life, which was only threatened on another occasion by a serious collision with a car, which happily she survived.

Jane’s death deeply affected the whole family. No-one was untouched, not even my Dad, who for years was always the first up every morning, and had to cope with her unsavoury night-time toilet habits. She had always seemed a trifle embarrassed by the necessity of having to cope with bodily functions, like an old spinster who couldn’t admit to actually doing anything that couldn’t be mentioned in private company.

In her early years she made attempts at hiding her misdemeanours by raiding the dirty washing basket for a handkerchief, a small child’s vest or some such thing and gently placing it over the offending waste matter. I’m sure my Dad doesn’t remember this with the same fondness.

Eventually, at the age of 15, her heart gave out. She spent a day quietly dying. It was obvious to all around that something was irreversibly wrong. No-one could bring himself or herself to call a vet that day, as inevitably it would have brought things to an unbearably abrupt end. My Mother decided to give her one last night among

her family and end her suffering the next day unless nature took its course.

After I had gone to bed, my brother took Jane into his bedroom and laid her on a large cushion so that he could be near her. In normal circumstances she regarded our bedrooms as her rightful night-time berth. She would visit each child, spending one or two nights with each of us every week. You couldn’t say no. You had no rights over space allocation in your own bed. Her fat little form would roll to the centre of the mattress and worm its way to the very best position. Somehow you would have to curl yourself round her and find extra spaces for your arms and legs. Forgiveness was easy because we truly loved her.

Of course I remember the fun and the friendship when the thought of parting seemed remote and unreal. For a dog she put up with a lot when my sister, my brother and I were very little. We used to dress her up in tightly-fitting old nylon party dresses and wheel her about like a baby in a dolls’ pram. She’d give us half an hour or so and then determinedly refuse to play any more. Yet she’d happily lie for ages under my brother’s head while he cat-napped during the day, using her as a pillow.

Working her daily routine around ours, in the afternoons she would sit outside the front gate in readiness for our homecoming from school and greet us with unbounded affection. She sought indescribable pleasures in the form of warmth and rest and comfort, and many a time she nearly cindered herself by lying on the narrow tiled hearth within inches of an open fire.

Food was her greatest downfall. After one successful raid on a six-foot Christmas tree, when she devoured all the foil-wrapped chocolates in one sitting, she attempted the same feast year after year in premeditated attacks, even though we had stopped using chocolate decorations.

Another time a cupboard door was left slightly ajar and almost a whole box of Winalot Shapes mysteriously disappeared. Of course no-one actually saw her do it, but for a good few hours afterwards a dog of small proportions looked very uncomfortable and rather sick, and not surprisingly turned away in disgust when she was tauntingly offered a biscuit.

On the last night Jane decided not to die in my brother’s bedroom. She must have struggled and gasped all the way down the long corridors of our bungalow back to her kitchen basket. I can imagine her desperately heaving herself along in a slow and painful progression to her personal sanctuary which became her deathbed.

I did not see her the next day. I could not bear to look. I did not know, until only recently, that my sister had seen her stiff and lifeless body and can remember it vividly even now. We are united in our grief for Jane, and cannot really talk about her without becoming emotional. I was, at the time, what could be described as a ‘bag of tears’ for a couple of sad weeks after her death, as I am now, writing this, 21 years later.

I heard the ghostly pad of her paws along empty corridors for a very long time afterwards.

Linne Matthews