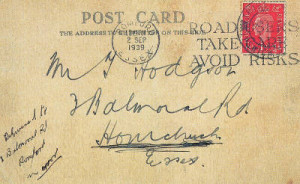

A SIX-foot-high wrought iron railing separated me from my father as we said goodbye on September 1 1939. I was assembled with the rest of the school in the playground at Forest Gate, East London, ready for evacuation. I had a cardboard label tied through my blazer lapel, a carrier bag provided by the government containing corned beef, condensed milk and chocolate, and my personal effects were in another bag which included my cousin’s toothbrush, but unfortunately not the recommended underpants which most lads’ parents could not afford. It was my first term at a new school so I knew no-one, and neither did we know where we were going. My father had given me a stamped addressed postcard to let them know where I was.

A SIX-foot-high wrought iron railing separated me from my father as we said goodbye on September 1 1939. I was assembled with the rest of the school in the playground at Forest Gate, East London, ready for evacuation. I had a cardboard label tied through my blazer lapel, a carrier bag provided by the government containing corned beef, condensed milk and chocolate, and my personal effects were in another bag which included my cousin’s toothbrush, but unfortunately not the recommended underpants which most lads’ parents could not afford. It was my first term at a new school so I knew no-one, and neither did we know where we were going. My father had given me a stamped addressed postcard to let them know where I was.

We boarded a train at Forest Gate and hours later arrived at Woodbridge, Suffolk, where we changed to a fleet of cream and red buses which took us to a village hall in Trimley.

Eventually, together with two other lads who were a year older than I, we were ‘chosen’ by our foster parents. They were kind and appeared elderly, but were also strict and very thrifty. Our carrier bags were handed over, never to be seen again.

Our bedroom contained two single beds pushed together. Unfortunately one bed was two inches higher than the other, so the one in the middle slept on a wedge, the one near the window was cold, and the one in the lower bed was warm but squashed. A rota was established fairly quickly and we took turns in each position.

Saturday night was bath night. Only one bath of hot water was provided, so the first in had a luxury bath, the second a lukewarm dirty water bath, and the last had to dig through the cold scum to find the water!

Saturday was also shopping day for groceries : I remember that F W Woolworth’s sold jars of orange curd for sixpence,

and a jar would last a week. Our supper was one slice of bread with either margarine, cheese spread or jam. In the early days I would often go behind the shed down the garden and cry because I was homesick.

Our new school was in Felixstowe, about two miles away, and my foster parents arranged with mum and dad for a local man to make a bicycle from second-hand parts for me. When it was ready I was delighted, even though it was black and had only a single low gear. My foster parents and the man who made the bike were very annoyed when my mother said she would pay the 7/6d purchase price over six weeks.

At the new school I befriended a local boy of my own age who suggested I move to their house in Felixstowe. I was delighted to accept the offer and his mother was a lovely kind lady who was the wife of a soldier and had four children. I was very happy staying with this family, even though my new foster mother must have struggled to provide us with sufficient to eat. The weekend dinners were invariably potatoes, cabbage and a large piece of suet pudding with a lump of margarine on the top. One weekend the soldier came home on leave and treated us to chips from the shop – oh, what luxury! During the week we had school dinners, and ‘seconds’ of sweets would be offered if available. On one day, I am ashamed to say, I went back seven times for suet and date pudding – how I suffered later!

A cycle ride was planned to Clacton (about 40 miles away) and we were all

enthusiastic. My foster mother prepared a small parcel of razor blade-thin fish paste sandwiches and I was off. I had eaten the sandwiches before I was half-way there, and I had no money or anything to drink except water.

Eventually we arrived and sunbathed on the beach at Clacton. Those lads who were solvent enjoyed Wall’s ice creams, but -I had nothing except water from a tap. I was exhausted as I began the journey home, and dropped further and further behind the other boys as my rests increased in length and frequency. Finally, I had to walk and push the bike. My foster mother was horrified when I eventually arrived home. I went to bed and stayed there for a week, and was spoilt as much as scarce resources would permit.

During my stay at Felixstowe I would help out in a small grocer’s shop. The small wooden building was crammed with goods, leaving very little room to move behind the counter. When I told my foster mother that the shop owner would often squeeze behind me to pass, but seemed to do it very slowly, she told me to stop going there immediately.

When the Germans invaded neutral Belgium and Holland, they finished up opposite us on the other side of the North Sea. The authorities decided to move us to the Rhondda Valley in South Wales. The train was routed via Cambridge, Bletchley and Oxford to avoid London (in case we all jumped off, I suppose). Being a rail enthusiast, I thoroughly enjoyed the experience, especially when we stopped at a country station in Bedfordshire, and we were served sandwiches, cake and lemonade by the W.V.S. We finally arrived at Treherbert very late, and I was ‘picked’ by a lovely couple who lived in a three-storey house which contained ‘The India and China Tea Company’ grocery store.

Mr. Shepherd, my foster father, worked in a colliery winding room, and at the end of each shift he would bathe in a tin bath in front of the fire where Mrs. Shepherd would scrub his back. I was banished from the room until ablutions were completed. Supper was frequendy accompanied by a

Both sides of the first postcard sent home by a bewildered refugee, salad of lettuce, cucumber, tomato and spring onion, all cut finely with scissors and seasoned with salt, pepper and vinegar.

It was at Treherbert that I was first introduced to faggots, which I still enjoy. Each Saturday morning Mrs. Shepherd would give me a penny for the pictures and a penny for sweets, providing I washed at least four times a day to remove the everpresent coal dust. One night I awoke to hear the air-raid siren sounding in the distance towards Cardiff. With vivid memories of the London Blitz, I was very frightened and ran into the two daughters bedroom. Vera was fifteen and Gwen

seventeen, two lovely girls of whom I was very fond. They let me get into their bed and this must have given Mr. and Mrs. Shepherd a problem. However, they soon convinced me it was quite safe to return to my own bed.

I still had my home-made bike, and a local lad offered me a Mars bar if I would lend it to him for ten minutes. I agreed, but he didn’t return until half an hour later and I started hitting him. A litde old lady dressed in black waded in to me with her umbrella shouting “leave our Welsh boys alone”.

After a brief interlude back home in Essex during a lull in the air raids, I was finally sent to Wellingborough. I was billeted with foster parents who had a son of my age, and we both attended the same school. Although we spent many happy hours playing with his Hornby train set, I was now 13 and becoming more interested in girls. (I remember one who invited me into an air raid shelter for the first passionate kiss of my life!) Unfortunately, round about this time I picked up head lice (perhaps from this lovely girl)! Even worse, I passed them on to my friend at home. My foster mother was alarmed and annoyed and washed my hair in a very strong solution of washing soda after a thorough fine combing.

After this, I wasn’t allowed to share the double bed, but had to sleep in a made- up bed in the bath. By this time I was quite tall and sleep was almost impossible whichever position I adopted.

Finally,my parents decided that I’d had enough, and should come home to attend a local school.

J. R Hodgson.