I recently heard that pawn-broking is making a comeback and, instead of seeking bank loans, people are once again raising cash by taking their treasures to Uncle, as the pawnbroker was affectionately known.

This news pleases me very much because I was a pawnbrokers daughter.

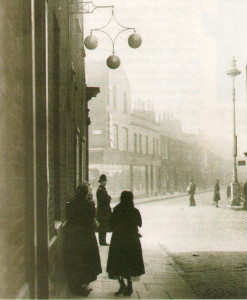

My father’s jeweller’s shop had been in the family for generations and was situated in the Earl’s Court Road in London. He jointly owned the business with his brother who didn’t spend much time in the shop, but my father was well served by his staff.

The window of the shop gleamed with silver. Inside, the glass counter glittered with jewellery and round the walls numerous clocks ticked and chimed the hours away.

Next to the shop front was a door over which hung three brass balls.

This door opened onto a passageway which led into the back of the premises – the pawn-broking department.

In the Thirties, it was quite common for hard up housewives to ‘pop’ the old man’s suit on a Monday morning and redeem it on the Saturday.

Once my father was caught out. He failed to check the bundle and, when opened, it was found to contain old rags!

Sometimes he got lucky. On one occasion a young teenage girl pushed a ring across a counter and said: “Will you lend me five on that?”

“Five what?” enquired my father. “Five shillings?”

‘Yes please,” replied the girl.

“I think,” said my father gently, “that I had better hang on to this and call the police.”

The girl fled.

The ring, an almost priceless diamond and emerald antique,

was never claimed. My father’s theory was that the ring had been lost for many years and forgotten and the girl, perhaps working as a housemaid had found it, hoping to get some money for it.

Sometimes valuables were pawned, not just for money, but for safety. On one occasion, a spoilt young man had been given a gold watch by an aunt, and his mother, nervous about having such an expensive item in the house, took it to the pawnbroker’s. When her son found out what she had done, he threw a violent temper tantrum and stupidly tore up the ticket. It was with grim satisfaction that my father told the obnoxious youth;

“Sorry, no ticket – no watch.” Howls of rage echoed round the Earl’s Court Road as the tearful woman escorted her unpleasant son from the premises, promising to buy him another gold watch. Virtually anything non-perishable could be pawned. I’m certain it was a means of raising cash on unsaleable items and unwanted gifts.

Our house was full of unredeemed pledges – jewellery, bric-a-brac and even small pieces of furniture. Once my father came home with a bolt of curtain material. It was an ugly shade of butcher blue, liberally patterned with vividly coloured birds and flowers. It was hideous. Out came the sewing

machine and my mother curtained every window and covered every cushion, even the screen got the treatment. Wherever I looked, I was confronted by unnaturally coloured birds and flowers.

Worse was to come. My father arrived home one day with an enormous pot of orange paint. My mother got to work with a paint brush and soon every door and window frame, even the storage jars in the kitchen gleamed bright orange, which clashed horribly with that awful curtain material.

Then a brand new man’s dressing gown appeared. In this garment my father lounged around the house trying to look like Noel Coward. Unfortunately it was vivid purple with magenta spots. For years it was like living in a migraine.

Came the war and, apart from his housekeeper, my father’s staff disappeared into various branches of the armed forces. Two elderly gentlemen came out of retirement to act as sales assistants, while the new shop boy was a lively octogenarian called Joe.

When I went back to the Earl’s Court Road, I had difficulty finding the place where the shop had been.

The premises had become an American style pancake house and I only recognised it by the fantastic old clock which still hung above the windows of the front room, where the housekeeper and a shop boy had once played shove-halfpenny.

I peered through the glass at the garish, psychedelic decor and tried to picture an old-fashioned shop window tastefully gleaming with silver. All I could see was the shades of my Victorian ancestors, their hands upraised in horror.

Peggy Jackson