I can’t help laughing at the I naivete of politicians. MP’s were outraged at reports that people under 16 were actually working for a living, one calling it ‘child slave labour’. How things have changed – or have they?

I was 14 in 1946 and working a five-and-a-half day week in a chocolate biscuit factory. Sometimes, instead of catching the bus home, I walked the five miles through quiet countryside. I wore my working overalls and became a walking snack. Thick blobs of chocolate had splashed on to them from the melting vats and I became an expert in picking off the chocolate that had not managed to get mixed with the lubricating oil we used on the machines.

My mother proposed a better job. I was still only 14 when I began working with the Co-op bakery delivering bread to individual households.

They had three methods of getting bread to the various parts of the city of Birmingham. For the inner city, they used horse-drawn carts – huge things that had hardly been modified from the wagons of the Wild West. For the suburbs, they used electrically-driven vans. Petrol trucks were used for the surrounding countryside areas.

I don’t think Diamond liked me. Not that I’d done anything to harm him. He just lashed out, suddenly, with his back leg and missed my chest by a fraction. It was a wicked foot. I’d just taken a great deal of trouble hammering into the bony hoof four knife-sharp wedges. Diamond was a cart horse, big, strong and brown with the white blaze on his forehead that gave him his name.

With fastidious care, I had finally managed to get all four hooves shod with the extra steel wedges to grip the ice and snow brought by the worst winter we’d had for forty years. I’d already fixed the halter and went back to the front of the stall, more gingerly this time, to pat his neck and persuade him to let me lead him on the mile

long walk along the busy, ice-covered main road to the bakery where the carts were kept. It was just 6.30 in the morning.

The covered cart that Diamond was drawing had been piled high with hot bread by seven o’clock. There were pound ‘tin’ loaves, double two-pounders, Hovis, batches, Allison brown and crusty cottage loaves.

Now it was five o’clock in the afternoon and the remaining bread was cold. But not as cold as the weather. It was biting! A brilliant afternoon sun had glazed over the snow and the snow crust was again ice. The stars were exceptionally bright but there were few people about to admire them in these urban streets.

It was Saturday. My older mate collected the money for the week’s bread at each house while I went ahead by a street or so, still making deliveries from

the large rectangular cane basket slung over my arm. I walked fast back to the cart for more bread. The floor of the driving box was some three feet from the ground. To reach it I had to use a single metal footplate fixed some 18 inches from the ground.

The slush on the footplate from the day’s constant use had frozen. My foot skidded on the icy metal and I fell headlong forwards. I lunged for something to hold onto and blindly clutched at the top part of Diamond’s back leg. Frightened by my sudden movements, the horse reared, pawed the air with his front hooves and bolted.

I found myself face upwards scrabbling for the driving box with one hand and, with the other twisted behind my back, held on to one side of the horse shafts. For long seconds, I was stuck between the shafts with my legs swinging just above the packed snow on the road

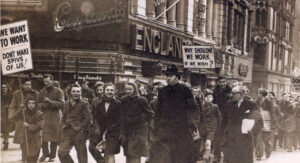

Top: Youngsters protest in Colmore Row, Birmingham, in 1948 about not being allowed to work for normal wages after the age of 14. Compulsory school leaving age had just been raised to 15.

rushing away beneath. Diamond’s powerful hind legs pounded next to my face. To let go would mean being kicked to a pulp by the flashing hooves I’d shod with snow wedges, and after that, run over by the giant cartwheels.

It seemed to take an age for me to claw my way from the shafts and up to the driving seat, as Diamond galloped on. At last I managed to gather his reins and pull him to a stop. I no longer felt the cold.

With the breath coming from his nostrils like two thick streams of fog, Diamond looked round at me with what I thought was a distinctive glint in his eye! ^0*

JohnSealey