Don’t give the game away,” I said. “Just tell her that someone’s dropped in to say, hello.” The manageress smiled conspiratorially and hurried to the staff-room at the rear of the store.

The counter girls twittered in anticipation as my colleague and I stood centre stage, as it were, in the middle of a small country branch of Woolworth’s’ like a couple of plain clothes policemen unsure of our facts. I fidgeted as I waited for the appearance of my war-time foster-mother, about to be lured from her tea-break to see who on earth had dropped in. I began to wonder if I had done the right thing.

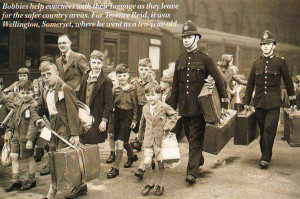

Having finished some business earlier than expected in nearby Taunton and with a couple of hours to spare before my London-bound train, I persuaded a locally-based colleague to drive me to Wellington where I spent the first nine months of the last war as a ten-year-old evacuee with my five-year-old brother, Des.

It was therefore something of a long shot to once again make contact, out of the blue, more than fifty years on, with the generous young couple who had taken us into their home within a few weeks of their wedding day.

how would I be received after such a long lapse of time: with interest, with pleasure, embarrassment, or even – too awful to contemplate – indifference? I had not long to wait, for marching (there was no other word for it) towards us from the back of the store, came a beaming manageress and a small, silver-haired lady in her mid-sixties with a wary look on her round, apple-cheeked face. Though the bloom of youth had, alas, long gone, I recognised her instantly.

“Hello, Mrs Vine,” I said, proffering my hand.

She took it without enthusiasm, her small hand limp in my grip. She eyed me and my colleague suspiciously, taking in the dark business suits. That there were two of us clearly foxed her. Were we, perhaps, bankers come to threaten foreclosure, or mortgage-lenders come to repossess?

“You don’t remember me, do you, Mrs Vine.”

Her eyes narrowed.

“Can’t say as I do,” she answered cautiously. In attempting to put her at ease, I gave her a clue which, on reflection, could have been better phrased. “I was last with you when you were expecting your first baby!” You could have heard a pin drop -Woolworth’s had never been so quiet!

Suddenly Mrs Vine twigged. She stabbed a finger at me and smiled for the first time.

“You’m be Terry Reid,” she said definitively. I nodded and grinned as we fell into an ungainly hug, whilst all around us cheered and clapped happily at this seeming serendipity. Then, almost immediately, Mrs Vine disentangled herself and enquired: “How’s your baby brother, Des?” I told her he was fine, six feet tall, married and living in Canada. Her instinctive concern for my brother confirmed my long-held suspicion that it was he, rather than I, who had excited the compassion that had found us wartime billets in the first place!

Mrs Vine then asked me how I had managed to trace her? I told of how I looked for the cottage where she began her married life the day before war was declared in 1939, only to find that it had disappeared as part of a wider housing development. When I enquired at a house, I was asked if I meant the young Mrs Vine or Granny Vine. I explained how, remembering her only as a young woman, it was a moment or two before I realised that it was, in fact, the Granny I sought and not her young namesake! I was then given her present address, informed that she worked in Woolworth’s and that Mr Vine was a window cleaner-cum-chimney sweep. During these explanations the manageress collected Mrs Vine’s

coat and handbag.

“Now, off you go,” she said. “The rest of the afternoon is yours.” She helped Mrs Vine on with her coat and handed over her bag.

“You sure tha’s all right?” Mrs Vine protested dutifully. By way of answer, the manageress, glowing with generosity, ushered us towards the door amid a profusion of thanks from me, as well as Mrs Vine. As we left, sporadic clapping broke out again among the rest of the staff.

Outside, Mrs Vine stopped, a forefinger pressed against her pursed lips: had I called at her house? I nodded. And her husband wasn’t there? I shook my head.

“In that case,” she said grimly, “I know where he’ll be.” With my long-suffering colleague and me in tow, Mrs Vine set off along the High Street at a blistering, light-infantry pace. After a hectic five minutes, we came to a wall against which leant a bicycle complete with ladder and bucket.

“I knew it!” cried Mrs Vine, turning sharply and unerringly towards a betting shop, with its dusty, poster-blank window and solid door. She barged in. My colleague and I exchanged nervous smiles and followed her.

The dim, drab, smoke-filled interior of the betting shop, with its bare floorboards, pockmarked counter and scattering of small round tables and rickety wooden chairs, resembled the saloon setting for the final shoot-out in a B-movie western. Only a flickering television set, the sound reduced to a murmur, undermined the illusion. Four startled men sat at one of the tables, frozen in the middle of a game of poker.

All eyes were on Mrs Vine, who had already begun to harangue one of the poker players, a small, wiry man, undeniably her husband. He sat stunned at the onslaught, caught red-handed playing poker with three of his cronies in the middle of the afternoon when all decent people were at work or collecting their kids from school.

Mr Vine appealed to his friends to back his assertion – which they did with varying degrees of conviction – that he had just that very moment popped in. His wife snorted in disbelief then, as

the dust began to settle, all attention turned to my colleague and me, two dark-suited strangers. Who were we? VAT inspectors? Or a couple of heavies from the DHSS hit squad?

The men were unsure, their uneasiness palpable.

“Well,” said Mrs Vine, suddenly remembering why we were there and pointing at me, “don’t you know who he is?”

“Can’t say as I do,” said Mr Vine, relieved at the switch of focus.

“He be Terry Reid!” said his wife in tones normally reserved for the slow-witted, conveniently forgetting her own fallibility not thirty minutes before!

“Well, I never!” said her incredulous husband.

He rose from the table, shook me warmly by the hand and said: “How’s your brother, Des?”

Over tea and cakes in the Vine’s sitting-room, we brought our respective lives up to date. Photographs of children and grandchildren were shown with pride, our lives having run very much on similar lines.

For my part, I wanted to authenticate memories of those far-off days when Sandy MacPherson hammered a cinema organ on the wireless almost non-stop and Hitler bided his time before hanging out his washing on the Maginot Line: a period inaptly dubbed ‘the phoney war’.

I remembered the young Mrs Vine being very firm but scrupulously fair, warm and loving with it.

She also took great care of my fretful five-year-old brother and saw to it that I was free to enjoy the pursuits of a ten-year-old.

As for Mr Vine, he taught me to roller-skate and took me to watch him play rugby for Wellington and his county, Somerset. Their basic decency and kindliness, still very much in evidence, did indeed authenticate happy memories of my short war-time stay in their hospitable home.

My colleague, as spectator, was both intrigued and moved. On the way back to Taunton, he asked what happened next? I told him that when Mrs Vine became pregnant, my mother brought us home to London until Hitler over-ran the Low Countries and the war began in earnest. What then?

“That,” I told my colleague, “is another story!”

Terence Reid