Mary Elizabeth Larkin or, as she was more popularly known locally, ‘Ma Larkin’, was my grandmother. She was the most colourful character I have ever met.

Mary Elizabeth Larkin or, as she was more popularly known locally, ‘Ma Larkin’, was my grandmother. She was the most colourful character I have ever met.

Born and raised in the area of Liverpool called Great Homer Street, she was one of the old breed of women used to hard times and harder work. Of Irish extraction, she was four feet eight in height, of slight build and poor eyesight. She habitually wore black ankle length dresses beneath which were layer upon, layer of equally long petticoats. The outermost of these contained a large front pocket in which she kept her purse.

At all times of the year, be it summer or winter, she wore about her shoulders a knitted shawl as did all the women of the area from which she came; giving rise to the local expression ‘Shawlie.’

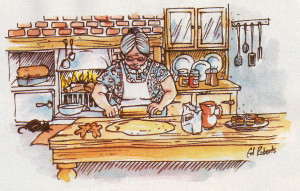

Her Saturday bread-making sessions were renowned as flour, salt and yeast would be deposited into a monstrous brown panmug and kneaded by hand into a seething mass of sticky dough. When ready, this would then be deposited onto a floured board on the well-scrubbed kitchen table and rekneaded for what seemed an age, accompanied by much puffing and panting. The mixture would then be left standing on a large brass stool before the open fire in the living room to rise.

After the appropriate lapse of time the mixture would be ‘Blessed’ to ensure success. This consisted of the ritual of cutting a cross in the dough before transferring it to the waiting baking tins. All my gran’s baking was done in a large cast iron oven built into the living room fire place. On these occasions it was my job as a ten-year-old to ensure that sufficient hot coals were continually available under the area of the oven.

Gran was the first woman I ever saw smoking and, of all things, a pipe. Every evening, usually about eight o’clock, out would come a white clay pipe, half an ounce of ‘Ogdens Thick Twist’, a box of ‘Pilot Matches’ and a pen knife. I’d watch fascinated, as she slowly and methodically took the knife and commenced to cut thin slivers of the sticky black tobacco from the bar.

This would then be rubbed very carefully between her gnarled hands until she was satisfied with the results, then carefully deposited into the pipe bowl with much tamping down. Once lit, she would blissfully lean back in her creaky old rocking chair, eyes closed, blowing huge clouds of blue smoke toward the ceiling.

Mondays were another important day to my grandmother. About nine o’clock, she would produce from the shed in the yard, her dolly tub, dolly pegs and a large wash board. No biological wash powders in those days, just a large packet of ‘Oxydol’, a bar of ‘Fairy Soap’ and a huge scrubbing brush to be used for shirt collars.

During the war years, at the height of the May Blitz on Liverpool in 1941, she would shake her fist at the heavens every time the sirens would sound and mutter: “God’s curse on that Mr Hitler. May he never know a minute’s peace.”

I never once remember her using the air raid shelter no matter how heavy the bombing even when my mother would beg her in tears. “If I’m going to die, I’ll die in my own bed and no German’s going to dictate to me what I have to do,” she’d reply. I never did see her give in.

Her spirit was never broken by anything or anyone right to the end of the war. One occasion in particular springs to mind. It was on the night of what became known locally as the ‘Night of the Big Raid.’

The bombers had come early that evening, and wave after wave of planes flew over the city as the night went on. At the top of the road where we lived was the railway goods yard known as the ‘Grid Iron’. This was the main marshalling yard for all railway traffic in the area. On that particular night, a train loaded with sea mines was in the sidings and took a direct hit from one of the bombs.

The resulting explosion wrecked many houses close to its centre and took out all the windows for a large area around. I remember hearing my grandmother scream and we all dashed upstairs to her room. I don’t know what we expected to find, but it certain-

ly wasn’t the sight I saw.

There was gran sitting bolt upright in bed, head and shoulders encased in a complete window frame, minus its glass, and not a scratch on her. Needless to say my mother was hysterical while my grandfather and I stood with mouths agape. “Don’t just stand there, get this thing off me. And our Nelly stop that screaming, you’ll give me a headache,” she snapped. My grandfather and I burst into peals of laughter at the thought of my mother giving gran a headache after what she’d already suffered. Well, that was Ma Larkin.

The incident only served to strengthen her resolve to curse Hitler all the more. Throughout her life, she was always the first to offer help to anyone in difficulty. Her strength and cheerfulness helped us all through those hard days and nights. One of her old sayings still spring to mind and I often smile when I remember them or tell them to my own family.

I shall always treasure her favourite saying which she would use when anyone did her a good turn. “God love you. May you be in Heaven an hour before the Devil knows you’re Dead.

Anthony Draper