September 3 1939 – Britain was at war! Waiting anxiously for my birth later that month at the Sussex Maternity Hospital, my mother must have wondered what the future held for her unborn child. As that future unfolded and the war progressed, life was better for our little family group than it was for a great number of folk – no evacuation, and we had a roof over our heads.

We were fortunate not to have any severe bomb damage to our house: the local gasometer in East Brighton was a prime target for bombing, but all we all suffered was cracked walls and a hole in the ceiling. Others were not so lucky: the nearby cinema was caught in an attack with great loss of life, including many children. Other areas of Brighton were flattened by bombs

at various times during those war years.

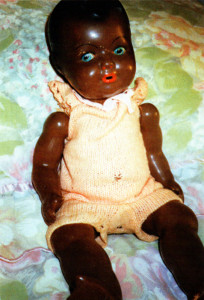

There were plenty of shortages and restrictions, and the shelter was very much part of one’s life. I started school in 1944 and can still remember the shelters in the school playground with their concrete steps leading to comparative safety underground. At my home the dining room had been made into a bedroom. Our Anderson shelter was set up with one double bed on top and another underneath, so that at night we could quickly slip under when the siren sounded. Apparently my black china doll – Margaret – had to come, too. I don’t think her cold china body wras too popular in bed!

Being an only child of older parents in wartime, 1 found those early years lonely and toys meant a lot, but they were in short

supply. There were many ‘hand-me-downs’ from friends and relations which meant much make-do and mend. Fortunately both my parents had the necessary skills to do this well, and as a result I became the proud owner of a renovated dolls’ pram along with other toys.

Food rationing caused much hardship, especially when visiting. Precious rations had to be eked out and taken to help the host household.

1 don’t remember us having eggs – perhaps one or two occasionally – but the National Dried Egg made very good scrambled eggs, and casseroled rabbit stood in for turkey for our Christmas dinner. At times apples and oranges must have been made available, especially for small children, but no bananas. I was seven or eight before I had the experience of eating a banana. What was this furry thing that came out of a yellow skin? Was it really good to eat? Initially I didn’t think much of it.

Sweets, of course, were rationed, and they had to last over several days – not eaten in one go! You had a slice off the Mars bar each day, a square of chocolate or a finger of Kit-Kat. What was an Easter egg? Once again I was seven before I found out. I remember it well! It was blue Bakelite and filled with Smarties. I’ve had a weakness for them ever since.

To help the war effort householders were encouraged to save their vegetable peelings, stale food and scraps. These were then put in the pig bins placed at strategic points in the street to aw’ait collection. Eventually these bins were replaced and the individual households had their own galvanised lidded buckets, which were put out to be emptied. This was completely independent of the weekly dustbin collection.

After six years of war the celebrations began! Street parties were everywhere. Down came the blackout curtains, street lights could at last cast their glow across the towns once more, and out came the ornaments, nick-nacks and other treasures from their wartime hideaway, stored in a big trunk at the back of the airing cupboard. What excitement for me when it was unpacked to reveal its contents!

The end of the war opened up the sea front again. The barbed wire barricade across the road was removed and we could venture along the coast road to see what was beyond. In spite of my young age I longed to know, and now at last I was to find out. The No. 12 Southdown bus took us along past Roedean School and St. Dunstan’s, the home for blind ex-Servicemen and women, still standing proudly above the cliffs – and then further along the coast to see Rottingdean, Seaford and Eastbourne. It would seem incredible today to imagine the excitement of a small girl who had been confined to her home town and knew nothing of the great big world outside.

The barbed wire was also cleared from the lower esplanade and the mines from the seashore. The Palace Pier and West Pier were repaired, haring been holed to deter

the enemy from landing. At last we could visit the seaside and discover the fun to be had there. Wall’s and Lyon’s opened up their ice cream kiosks on the two piers and along the sea front. I had my first choc-ice!

The sandbags and gun emplacements were removed from the upper esplanade. No longer would the soldiers call out: “Hello, Blondie” to the small fair-haired girl being taken for a walk along the sea front on those occasions when it was open to us civilians.

Now it was all opened up, and our lives were no longer governed by the air raid sirens. The gas masks were discarded, shelters were dismantled and our beds were taken back upstairs, which gave us back our dining room. I was to learn to live in peacetime!

This was all a long time ago. Now we’re free to come and go as we please – to travel far and wide. We have such a great selection of food, clothes and consumer goods in the shops that sometimes we’re spoiled for choice. My grandchildren are growing up in this world and can’t imagine the shortages and problems of war, and I just hope they never will!

I still have some of my childhood belongings from the past. Margaret the black china doll is safely packed away with other treasured dolls from my childhood. Several of the nick-nacks belonging to my parents adorn the shelves of my home. The dolls’ pram went out many years ago, but Best of British (January 1997) brought memories of it flooding back again.

A trip down memory lane is certainly something in which the magazine excels!

Betty Byford