A small aerodrome at Stanley Park, Blackpool, was probably responsible for an early interest in aviation. For most of the 1930s 1 was at a convent boarding school less than a mile away. When I was given a Kodak Brownie Junior for Christmas one of the first photographs I took was of Handley-Page Harrow bombers at an Empire Air Display there in 1938.

Most of the nuns were sympathetic, even running to an Encyclopaedia of Aviation as a prize one year, but Mother Mary Paula, our maths teacher, had no time for the ‘laziest girl in the school’ as she called me. I hated maths, and from a desk near a window the view was more attractive than the blackboard.

When the wind was in the right direction planes skimmed the convent roof before landingjust down the lane, and their registration numbers had to be memorised before adding them to my collection when the teacher wasn’t looking. Strangely enough, I did listen to algebra lessons, always fascinated by the substitution of letters for numbers, especially when M. M. Paula, in a rare light-hearted moment, proved unequivocally that one equals two. I still haven’t fathomed that one out!

After school in 1940 came secretarial college in order to have something to offer the WAAF when the time came. Languages had always been a favourite subject, so, shunning unintelligible book-keeping, I gained instead the Higher Commercial Education Certificate in French (distinction in the oral portion!) and made sure that my Italian did not get too rusty.

On St. George’s Day 1942 I became a WAAF, and after a series of written tests to determine our capabilities I was classed Computer Clerk and drafted to the Italian Air Force section of secret intelligence at Bletchley Park. At first it was deadly boring for us ‘stooges’, ie trainees, spending tedious hours matching patterns, something a modern computer would do in a flash, but I managed eventually to become a code-breaker, a much more satisfyingjob.

When Italy opted out of the war I was transferred to the Japanese section where I helped to start, and later was in charge of, a giant index of the Japanese Army Air Force. Fortunately I had been blessed with a photographic memory, so information on units, locations, aircraft and even individual pilots stayed in my mental computer long after I had written them down.

Promotion was fast at Bletchley if you were competent, as high grades of secrecy were not accessible to lower ranks. Thanks to that rule I was commissioned at 21, and a year later was posted to the US Pentagon with instructions to show the Americans that collating information could be done faster and more efficiently by human computers than all their mechanical gimmicks.

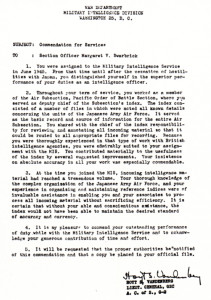

At the end of that trip, cut short when the war finally ended, I received a letter from General Vandenberg, of the American Intelligence Service, of which I am inordinately proud. I deeply regret that the Official Secrets Act forbade me to show it to my mother, who never did find out what her eldest daughter had been up to during the war. And how I would love to have seen M. M. Paula’s face when she realised that watching aeroplanes instead of struggling with Isosceles triangles had actually stood her laziest pupil in good stead after all.

Margaret Finch